Foodfight! and How Not To Make a Movie

Threshold Animation Studios’ 2012 animated feature film Foodfight! (Lawrence Kasanoff, 2012) is considered by critics and the audience as one of the worst animated productions of all time. But while Foodfight! performed poorly at the box office, in home video sales, and in critic and audience reviews, the film is often overlooked as a perfect example within the animation industry of everything that can go wrong when making an animated film. To understand its colossal failure, context in how, why, and when it was created is essential.

Foodfight! is the brainchild of Threshold Studios producers Lawrence Kasanoff and Joshua Wexler, who, after the success of Pixar’s Toy Story (John Lasseter, 1995), were inspired to create their own computer-animated feature. A movie about a collection of grocery store mascots coming to life at night and having to fight a generic brand was beginning to formulate within the studio. This idea, drafted as a treatment in 1997 (Kasanoff and Wexler 1997), was titled “Foodfight,” though they also discussed ideas such as Mascot, Arcade, and Sunday Comics Capers, all with nearly identical premises (Weiss 2024). Production was funded through an investment by Korean company Natural Image along with a facilities sponsorship by IBM facilitated by producer George Johnsen. Threshold had planned for the rest of the film’s budget to be filled in by presales and loans from their projected success (Taub 2004). Foodfight! had roughly 50 mascots, ranging from Mr. Clean to Twinkie the Kid, signed on to appear in the film (Aristizabal 2001). The end goal of the film, it seemed, was to make the highest amount of money and open as many sponsorship and merchandising doors as possible. Immediately upon announcement of the film’s production, there was criticism in the media about its consumerist message to children (see Ruskin 2001). Since Spielberg’s E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, paid product placement had been a fairly common tool within the entertainment trade. In the case of E.T., Reese’s paid for their product, Reese’s Pieces, to be featured within the film to gain exposure and for their product to be associated with a popular and successful property. When Spielberg’s film was released, Reese’s Pieces sales went up 66 percent (see Mazur 1996). Ironically, brands that were featured in Foodfight! did not pay to appear in the film (Aristizabal 2001). While brands often depend on a film’s success to make them money, Threshold reversed this relationship, instead depending on the brands’ fame to make the film a success.

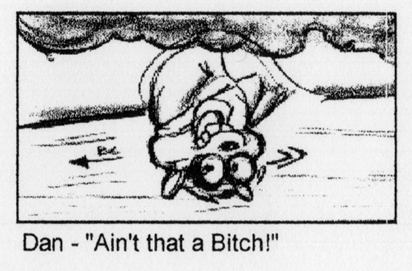

Visual development on the film started in early 1999, with Jim George, previously an animator for Walt Disney Animation Studios, hired as the film’s character designer. However, George took a much larger role beyond doing key designs; he co-directed the film’s sizzle reel, a 10-minute reel of animation meant to be pitched to investors, with Johnsen. Starting around 2000, the animation was undertaken by animators such as Jeremy Yates, Brad Herman, and Neil Fordice among others using Lightwave, a publicly-accessible animation programme. The script, written with a PG-13 to R rating in mind, was being adapted by Johnsen as a Looney-Tunes-inspired film recalling the days of golden age animation. Early crew members recall that early in development the comedy was intended to be similar to MAD Magazine or Wacky Packages. In storyboards and scripts for the film, characters are depicted cursing and making dirty jokes (see Fig. 2). The amount of time it was taking to animate, however, was troubling to Kasanoff, who was acting as the head producer and writer. As stated by his co-workers in a private conversation, Kasanoff struggled to understand the animation pipeline or trust his peers in directing and animating it.

In 2004, it was reported that the entire film, assets and all, was stolen in an act of “industrial espionage” during the Christmas season of 2002. While some crew members recall being questioned by the FBI after the theft, according to my own conversations with those involved in the film's production, those higher up in the chain have severe doubts about whether the theft actually happened. Given that assets from the film were later discovered with several backups by script supervisor Loressa Clisby in 2005, the claim stands on little evidence. Later in 2004, Kasanoff decided to scrap the majority of work on the film, along with firing the majority of his team, in order to animate Foodfight! with then-popular motion capture technology. Working in the House of Moves motion capture facility, Kasanoff, taking over as director, had thought that using motion capture would be the same as directing a live action film. An entirely new team was hired, now working in Maya, to remodel, rig, and animate the characters (Clisby 2024). The script went through several revisions and in 2005, a cast was settled with Wayne Brady, Eva Longoria, Charlie Sheen, and Christopher Lloyd.

Crew members recall production on Foodfight! being a catastrophe in regard to levels of professionalism. Investors, having been promised that the film would come out as early as 2002, were growing impatient with the film’s sluggish development. Upon repeated visits (one claim being the film was funded by the Japanese mafia), crew were instructed to start rotating models in order to look like they were creating something. When asked to be shown what was made for the film thus far, Kasanoff allegedly screened Hershey’s Really Big! 3D Show, a theme park attraction they had animated in 2001. Other complications, such as Kasanoff’s dog defecating around the studio (Clisby 2024, 3; Weiss 2024), and Kasanoff making vague comments such as “make it more awesome” or wanting a shot to be re-rendered from a different angle within seconds, were also making production difficult. Both Clisby and concept artist Michelle Renee Hall recall Kasanoff fawning over a nude render of antagonist Lady X (see Fig. 3), to which he moaned upon seeing it (Clisby 2024, 4).

Kasanoff’s constant use of masculine and misogynistic humour dates back to Threshold’s website The Threshold (and its sister site, Threshold Babes) as early as 2000 and is clearly in use in Foodfight! both on and off-screen. In one particular sequence, Lady X visits Dex Dogtective in a sexualized school-girl outfit with skin-tight arm-length plaid gloves. Many of Foodfight!’s most infamous traits are present within this scene, including bad textures, stiff motion capture, and the usage of corny puns such as “holy chips” in place of cursing. Lady X’s movements and the dialogue itself is hardly appropriate for a film that was later intended to be advertised for children. Given the context of the character’s studio-exclusive nudity, it is hard to say Lady X existed as anything else than an erotic sex symbol.

In mid-2005, art director, texture artist, and catch-all crew member Gary Clair was asked to edit together a workprint of the film so investors had something substantial to look at. Until this point, storyboards were slim due to Kasanoff’s heavy reliance on motion capture. This resulted in a workprint being cobbled together with animation from the scrapped version of the film along with quickly made storyboards using chopped up renderings of the characters on top of stock photos. This workprint was likely not effective, given that on September 20th, 2006, investors signed a promissory note requiring Threshold to complete the film or have it taken away from them by March 7th, 2008 (“Notice of Public Sale” 95). Still, hope for the film’s success was strong, and merchandise such as toys and chapter books were reaching store shelves. Regardless of these promises and high hopes, however, companies that had signed on to have their brands appear in the film were backing out (Weiss 2024).

During 2007, publicity stills were finally making their way to the public to less than ideal responses. Due to the incompetent and rushed production, rendering often looked unfinished, textures were low quality, and models lacked sufficient subdivision. By the time the promissory note lapsed, the production was taken over by the Fireman’s Insurance Fund, who hired a new, small team to finish the film as quickly as possible. According to the team hired by Fireman’s, the film was completed sometime in 2008. The film sat in limbo for those next few years for unknown reasons, but likely due to the impossibility in finding a distributor willing to take it. In 2011, the film, its assets, and the copyright were up for auction with a starting bid of $2,500,000 (“Notice of Public Sale” 95). No one bought the film, leaving ownership to Fireman’s, later absorbed by its parent company, Allianz. In 2012, the film was finally given a theatrical and home release by Boulevard Entertainment in Europe and Viva Pictures in the United States.

Foodfight! was released to great scrutiny. Cartoon Brew, who had been following the film’s difficult development since 2004, took great delight in tearing the film apart (see Amidi 2013). Without a theatrical release in the United States and greatly relying on profits made from home video releases, Foodfight! was rightly considered a financial failure. However, in contrast to its demise, many crew members went on to work on more successful material. Many animators from the Lightwave crew went to work for the game studio Naughty Dog while editor Craig Paulsen went to work for Warner Bros. Jim Carbonetti, stereoscopic supervisor on Threshold’s Hershey project, recalled to me that working at Threshold was good for the crew, because they knew that no job could be any worse. Yet other members today refuse to speak about their experience on the film, many of which choosing to opt it out of their resumes entirely.

It's no surprise that Foodfight! was a dismal failure. However the majority of the audience and critics simply dismissed it as a failure due to the concept and its poor style of animation. However, when the film was still being directed by George and Johnsen and animated in Lightwave, it seemed, for that moment, Foodfight! actually stood a chance. That chance was demolished when someone with a high influence took control of a project that he had no prior experience in being able to direct. Not necessarily for the good of the project or his team, but for the good of control and potential profit. Given recent discussions with “executive meddling” regarding Disney/Pixar’s television series Win or Lose (2025-) as well as Wish (Chrus Buck & Fawn Veerasunthorn, 2023) and Warner Bros.’ upcoming Coyote vs. Acme (Dave Green, 2026), Foodfight! stands as a cautionary tale in what not to do when creating an animated film, but a tale not all too unique from the others.

**Article published: January 23, 2026**

References

Amidi, Amid. 2013. “Why ‘Foodfight!’ Cost $45 Million And Was Still Unwatchable.” Cartoon Brew. August 8, 2013: https://www.cartoonbrew.com/feature-film/why-foodfight-cost-45-million-and-was-still-unwatchable-87138.html.

Anon. 2011. “Notice of Public Sale.” The Hollywood Reporter 33. September 23, 2011.

Aristizabal, Cynthia. “Threshold builds a big-screen brand-a-palooza.” Kidscreen, 1 June 2001, https://kidscreen.com/2001/06/01/30907-20010601/.

Carbonetti, Jim. Interview. Conducted by Jacob Pruitt. February 20, 2024.

Clisby, Loressa. 2024. “Empire Magazine Statement.” Internet Archive. June 2, 2024, https://archive.org/details/loressa-statement-for-empire.

Crew Member 1. Interview. Conducted by Jacob Pruitt. April 9, 2024.

Crew Member 2. “Discussion regarding Foodfight!” Private message. March 25, 2024.

Crew Member 3. “Discussion regarding Foodfight!” Private message. February 16, 2024.

Kasanoff, Larry, and Joshua Wexler. Foodfight. PA0001331776. U.S. Copyright Office, 1997.

Mazur, Laurie Ann. 1996. “Marketing Madness.” E Magazine: The Environmental Magazine 7, no. 3.

Ruskin, Gary. “Commercial Alert Criticizes Movie-Length Ad Targeted at Kids.” Public Citizen’s Commercial Alert, 7 May 2001, https://web.archive.org/web/20160310145717/http://www.commercialalert.org/issues/culture/movies/commercial-alert-criticizes-movie-length-ad-targeted-at-kids.

“The Threshold Network”. The Threshold December 2, 2000: https://web.archive.org/web/20010424142104/http://www.thethreshold.com/.

Taub, Eric. 2004. “For This Animated Movie, a Cast of Household Names.” The New York Times. May 17, 2004: https://www.nytimes.com/2004/05/17/business/media-for-this-animated-movie-a-cast-of-household-names.html.

Weiss, Mona. Interview. Conducted by Jacob Pruitt. February 15, 2024.

Biography

Jacob Pruitt is a student at the University of Texas at Dallas, Harry W. Bass Jr. of Arts, Humanities, and Technology. His focus is on film and design, but he loves learning and writing about various subjects, such as animation. Earlier versions of this text were developed with the help of Amy Grieshaber, Assistant Professor of Instruction, and peers from the Animation Studies course.