Refracted Reality: The Truth of Fantasy in The Wedding Veil of the Proud Princess

When I first encountered the part of L. M. Montgomery’s 1911 book The Story Girl that contained the tale of “The Wedding Veil of the Proud Princess,” I was struck by a sense of recognition. As a director and storyteller myself, it felt less like discovering a story and more like remembering one I had always known, a fairy tale so archetypal that it seemed impossible it was not already part of the shared cultural canon. Its setup of a beautiful princess who declares she will only marry the king who conquers all kings, and the payoff of this turning out to be Death himself, has all the hallmarks of a medieval fairy tale.

There is another important resemblance that “The Wedding Veil of the Proud Princess” makes to well-known ancient tales. A woman endlessly working on her wedding veil while remaining unwed echoes Penelope from Homer’s Odyssey (composed c. 8th century BCE), who wove and unwove a funeral shroud each night to delay choosing among her suitors while awaiting her husband Odysseus’s return. Likewise, a beautiful princess who politely rejects high-ranking men by giving them impossible tasks recalls Princess Kaguya, the protagonist of The Tale of the Bamboo Cutter (Heian-era Japan, c. 10th century CE), who was discovered as a baby inside a glowing bamboo stalk and later tested her suitors with impossible challenges to avoid marriage, ultimately returning to the moon rather than choosing a husband.

However, Montgomery’s tone throughout “The Wedding Veil of the Proud Princess,” as well as the dialogue between the characters who hear the tale as told to them by the titular Story Girl, frames this story as a cautionary parable about female pride and its inevitable punishment. But I felt a dissonance between the author’s words and the images they conjured in my mind. If the archetypal parallels mentioned above can be validly drawn, then the Proud Princess’s real intent in setting an impossibly high goal for her would-be husband was not to self-aggrandize but to avoid marriage altogether.

Of course, there is an important detail that sets the Proud Princess apart. Her proclamation inspires kings of all lands to go to war, which leads to great suffering for all. It was this tension, the Princess’s defiance causing both admiration and destruction, that made me reflect on how stories convey meaning and how perception can differ from narration. These reflections form the heart of this blog - a creative exploration of how I translate narrative gaps, character complexity, and moral ambiguity into my own animated work.

The Wedding Veil of the Proud Princess (Anna-Ester Volozh, 2024) - Trailer

Nonetheless, in my mind’s eye, the Proud Princess was not simply an outright villain to be humbled and punished. Her defiance seemed less like destructive pride than a refusal to be consumed by the only role her world offered, that is, to pass from being her father’s property to another man’s. Death, when he finally arrived to claim her, did not feel like punishment. He was, paradoxically, her liberation.

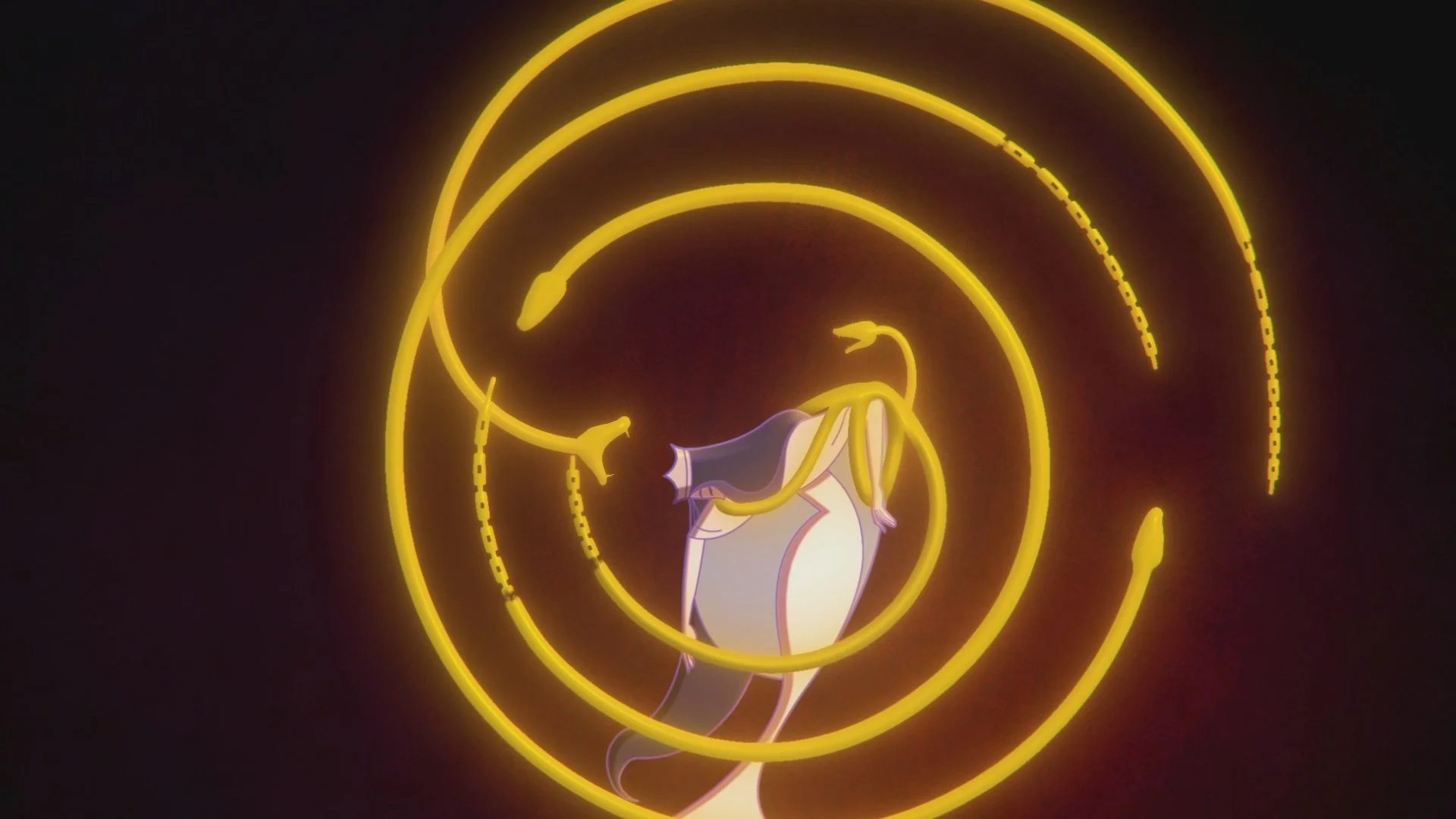

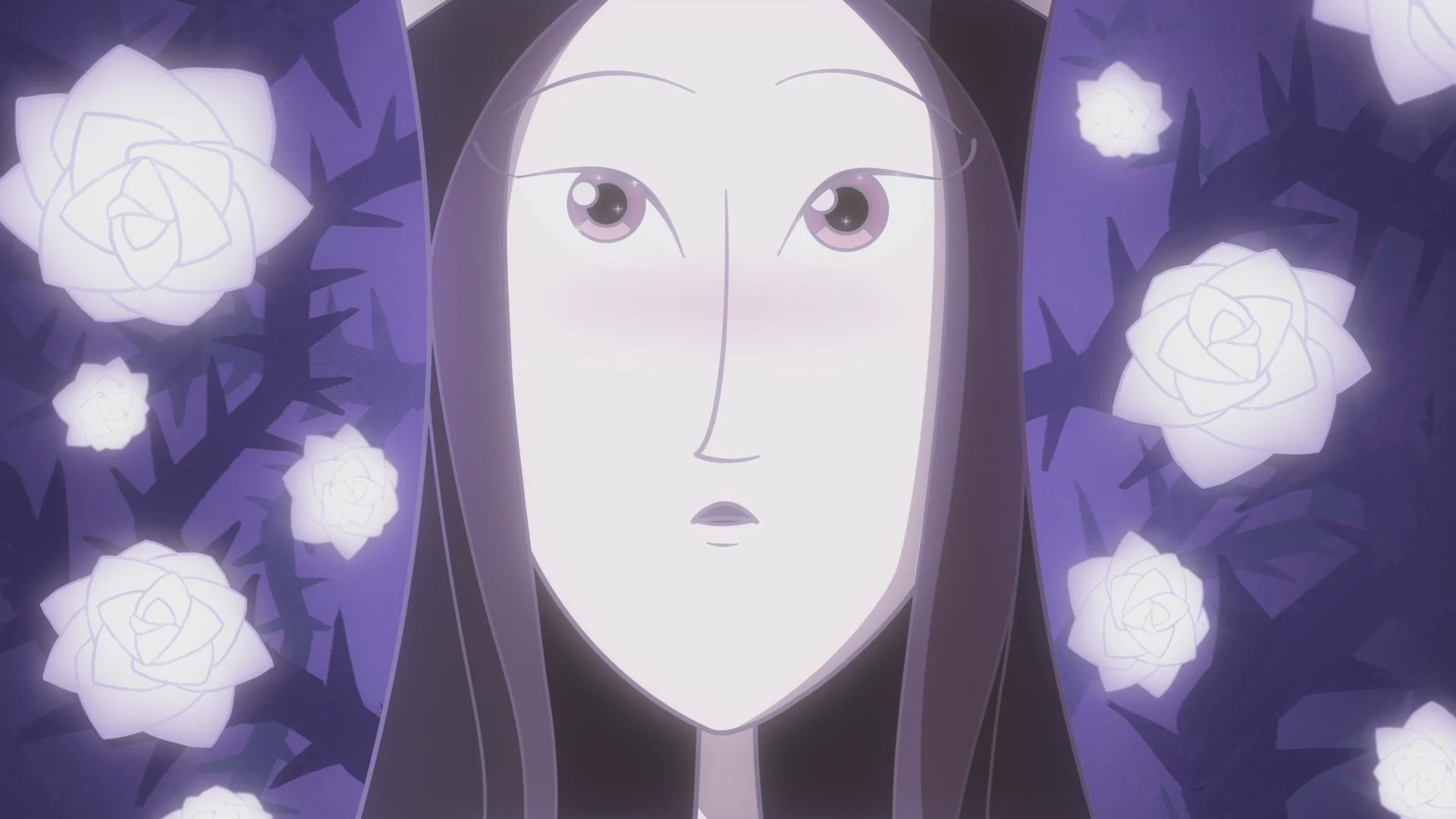

By reflecting on the dissonance between how the narrator presents the story and how I perceived it, I began to consider how my own creative work could explore these gaps. I wanted to translate that tension into visual storytelling, showing that narrative perception is never singular and that viewers can experience multiple truths simultaneously. In my animated version of Montgomery’s tale (see above), the narrator’s voice remains very close to the original text, just slightly abridged. The visuals, however, tell a different story. Where the narration judges, the imagery sympathizes. For example, the suitors’ golden engagement rings become chains and snakes through the Princess’s subjective experience (see Figs. 1 and 2). Through this layering, I invite the audience to decide which story feels truer, or perhaps to find a third meaning of their own.

This duality is uniquely suited to animation. Animation allows metaphor itself to become visible because of the higher suspension of audience disbelief inherent to the medium. Abstract imagery can reveal a character’s inner state without explanation or reliance on facial expressions alone. For instance, when the princess hears the words “free forever more,” the thorny vines that symbolized her mistrust of yet another suitor erupt into delicate white flowers, a fleeting glimpse of the world she longs for (Figs. 3 and 4).

Perhaps such a glimpse is what J. R. R. Tolkien describes in On Fairy-Stories (1939) as “Recovery,” a way to see ordinary things with renewed clarity. In this sense, fantasy does not oppose reality, it refracts it. I agree with Tolkien and think of fantasy as a genre not as a retreat into artificiality, but as a way of seeing the real world more deeply. Most crucially to me for my own work, fantasy is not an artificial product of my imagination. It is an authentic depiction of the tangible outside reality the way it is represented in my mind. Put simply, fantasy is how I understand the world. This understanding directly informs my own work: in my films, I aim to make visible the patterns, emotions, and truths I perceive in reality, translating them into imagery and narrative that allow viewers to see the familiar in new ways. Every creative decision, from character design to symbolic visual motifs, is guided by the desire to render internal perception as tangible experience, so that the audience can encounter both reality and imagination simultaneously.

In my own adaptation of The Wedding Veil of the Proud Princess, this idea takes literal form in the final image. After Death carries the princess away, the people of her land look to the sky and see her veil as sweeping white clouds. Here the fantasy and the physical world meet. The clouds are real, part of nature’s vast, ancient beauty, and yet they are also story. After all, film, like all art, is a kind of worship song to me, but I must never mistake the song for the thing it praises. The true object of wonder is our 13-billion-year-old universe, the beautiful planet Earth, the living systems of nature that will outlast any film we make.

I hoped the film would encourage viewers not only to question the specific narrative presented within it but also to question all narratives they encounter in life. This intention shaped many of my creative decisions. For instance, where the narration describes Death’s horse as “white”, I deliberately chose to show it as having a dark-coloured coat in order to inspire doubt in the narrator’s reliability. Or how all the human kings vying for Princess’s hand are designed to look exactly the same, not in the literal sense of them all having identical appearance, clothes, cultures, but to imply that they are all the same psychologically.

The Wedding Veil of the Proud Princess.

Ultimately, the film explores a single question: what price are you willing to pay to stay true to yourself? By presenting a sympathetic view of a character who chooses the most extreme answer to this question, and who is condemned by the narrator within the story itself, I wanted viewers to start wondering. Is the Princess selfish and irresponsible? Is she delusional, causing devastation to chase a mirage? Or is there something else entirely at work?

There is no hierarchy among these interpretations. None of them cancels out the others. My goal is not to provide a definitive answer but to open a space where metaphor can be personal and fluid. Animation, with its fluid boundaries between the real and the imagined, intensifies this ambiguity. It allows metaphor to take on literal form. Dreams, memories, and emotions can coexist without hierarchy, blurring distinctions between outer reality and inner truth. This quality of the medium directly supports my aim: not to provide a definitive answer, but to open a space where meaning remains personal, shifting, and alive.

Speaking of community response, two viewer comments stand out most vividly. The first came from a commenter who told me they planned to share the story of the Proud Princess with the children in their care as the babysitter the next time they looked up at the clouds described in the film. The second was a photograph shared with me by a loved one, a sweeping blue sky filled with intricate, delicate clouds, accompanied by the note, “Look! Just like in your film.”

These responses meant so much to me because they showed how the film had folded itself back into lived experience. The story is not an isolated work of art but part of an ongoing exchange between reality and imagination.

In the end, when I create fantasy animation, I am not escaping the world but engaging with it more deeply. The clouds in the sky are real, and so are the stories we weave about them. Through film, I hope to remind myself and others that both are worthy of wonder.

**Article published: February 13, 2026**

Biography

Anna-Ester Volozh is a London-based director and producer known for their work in independent 2D animated film. Born in Moscow, they first earned a Bachelor’s degree in Economics, then shifted to pursue their creative calling with a Master of Arts in Animation from Arts University Bournemouth, graduating in 2013. In 2015 they founded Dragonbee Animation, a boutique studio in London making both commercial and festival-oriented animated content. Since 2024 they returned to freelance work, combining their studio experience with the flexibility of smaller collaborative and solo projects. Their films include Johanne (2017), The Last Cloudweaver (2022), and The Wedding Veil of the Proud Princess (2024). Anna-Ester is queer and nonbinary. They can also be found at https://anna-ester.com/ and https://www.instagram.com/dragonbee.animation/.