Tricky Women, Animation, and Fantasies of the Monstrous Feminine

The Tricky Women International Animated Film Festival, screening works by female and genderqueer artists, aspires to the fantastical vision, “to imagine a world that is different from the one we currently live in.” Given its radical agenda, it is remarkable that host city Vienna has consistently supported this event for twenty-five successive years in some of its finest cinemas, attended by diverse audiences and sponsored by prestigious patrons (Fig. 1). The strategic positioning of the festival to coincide with International Women’s Day welds it into feminist history. The ambition for transformation is proposed at both the organisational level, the shared director role broadening strategies for inclusion, and the programming, with films characterised by fantastical themes of transgression, mobilised most persistently through the figure of the monstrous female body.

The representation of the female as monstrous is analysed by feminist scholars largely in relation to psychoanalytic perspectives. Rosemary Jackson observes the prevalence of the fantastical in 20th century literature as a symptom of a repressive society, monstrous disfigurement occurring through imagery of bodily disintegration, splitting or self-multiplication, the destabilisation of coherent character subverting literary conventions (1981, 90). In her study of the representation of the monstrous in cinema, Barbara Creed similarly posits that the greatest horror relates to the female genitalia and scenes featuring offscreen or dark space point to the invisibility of the womb (53, 1993). The coding of the female body as a cavernous space is further linked by Mary Russo (1994) to the aesthetic of the grotesque, which she traces back to the grotto like decorative intermingling of vegetation, human and animal forms. Departing from Creed’s focus on male directors, she offers examples in which hybrid monstrosity is represented in artworks by female artists.

Animation is frequently composed from disparate materials such as drawing, textiles, clay and live action, a hybridity that is central to the representation of the monstrous feminine. Such use of mixed media to tackle monstrous -feminine themes characterised work by UK female animators of this period: the castrating giantess in Joanna Woodward’s The Brooch Pin and the Sinful Clasp (1991) (Fig. 2) and the witch who induces men to menstruate in Vera Neubauer’s Mid Air (1986) (Fig. 3). This proliferation of animated films that subverted negative myths and taboos surrounding the female body merited three editions of BFI produced VHS series, Wayward Girls and Wicked Women (1993) after fantasist novelist Angela Carter.

More recently, the focus on the monstrous as fantasy of the feminine has been reevaluated by several female scholars, writers and artists, but with a focus on artwork by female practitioners, including Creed’s own updated return to the monstrous-feminine (2022). Catherine McCormack examines art historical and mythological examples of feminine archetypes to propose that the threat posed by powerful women, such as witches and suffragettes, has been contained through their depiction as voraciously sexual, dirty beasts (2021, 173). McCormack refers to the giant sugar-coated sphinx-like sculpture by Kara Walker, also an animator, A Subtlety, or the Marvellous Sugar Baby (2014) (Fig. 3). The sphinx’s feminine mysteries are represented here as the allure of the sweet material is contradicted by the repelling gaze that bears witness to the misery of sugar plantations (McCormack 2021, 203).

Lauren Elkin locates her own inquiry precisely in the figuring of the monstrous in art, which she notes is a method employed by female artists for taking up cultural space (2024, 7). Elkin refers to celebrated Austrian Maria Lassnig, significant as 2023 Tricky Women festival guests were treated to a guided tour of the late Lassnig’s studio. In Self-Portrait as Monster (1964) her face bright pink and shapeless through age, with eyes closed and lips pouting in readiness to kiss typifies Lassnig’s methods of self-parody. The older woman, considered as threatening due to her wisdom, has been cast as a lusty, yet sterile, repulsive witch (McCormack 2021, 212) a negative stereotype subverted through Lassnig’s exaggeration.

Animators continue to reclaim and destabilise negative fantasies of the monstrous feminine, using methods of satire, subversion and formal innovation. The 2025 Tricky Women event encouraged such exploration through programmes (Transgressions; Tricky Monsters and Hypercapitalist Nightmares), as well as offsite exhibitions. I will discuss just a few of the many works in the event to give a snapshot of how varying animation methods are deployed to consider this myth.

The figure of the hag, satirised by Lassnig, finds further expression in Isa Fraga-Abaza’s Birth Controlled (2024) in which a character exists only in relation to her fertility. As with Lassnig, exaggeration is the method used to describe a young woman’s body, old before it’s time, excessively droopy, drawn in black cartoon lines that describe folds of slack skin, loose pendulous breasts and enlarged teats. A commentary on women’s rights and a satire of reality TV, here it is the fictional audience that behaves monstrously.

In Clara Trevisan’s stop-motion short Mother of Dawn (2024) a giant 3D hairy, fanged and clawed puppet creature is surrounded by sparkling treasures, the darkness of her lair enhancing the shine of her beautiful jewels and glowing astrological map of the stars. The film’s nocturnal, magical mood can be considered through Creed’s figure of the vagina dentate (1993, 37) the monster’s gaping dark maw with sharp teeth and her collection of bones provoking anxieties of the castrating female. I Smell a Mouse (Liti Yli-Harja, 2024) engages the dynamic of excess, a rodent infestation of impossible proportions allegorising a character’s inability to contain her grief (Fig. 4). The expressive power of felt puppets enhances the discomfort of emotional breakdown in public, the type of eruption that Elkin observes has been considered to be disgusting in women (Creed 1993, 14).

If the devouring, smothering maternal figure is the stuff of horror, equally the independent mother who rejects her designated caring role is cast as transgressive because she poses a threat to order. The short Mama Micra (2024) narrates director Rebecca Blöcher’s personal account of her mother’s unconventional lifestyle (Fig. 5). The confrontation with often painful memories is made approachable through the distancing device of puppets, the use of soft felt giving the strong mother’s face an appearance of gentleness that indicates her vulnerability. While in the horror genre female characters are typically punished for non-compliance (Elkin 2024, 14), it is Blöcher’s own independence that gives her the freedom to direct her own film.

Jackson proposes that bodily processes of dis/re-integration, prevalent in fantastical literature, relates to disturbances in processes of ego formation (1981, 83). The gymnastic female figure in Glazing, Lilli Carré, (2021) undergoes such physical extremes in order to occupy as much of the frame as possible. Her cartoon drawn body stretches and her arms multiply, like the Indian goddess Kali, with eight or more twisty limbs. The plasmatic quality of animation is exploited here to depict fantastical more than human forms, an unruly female body and also the exploration of a female ego.

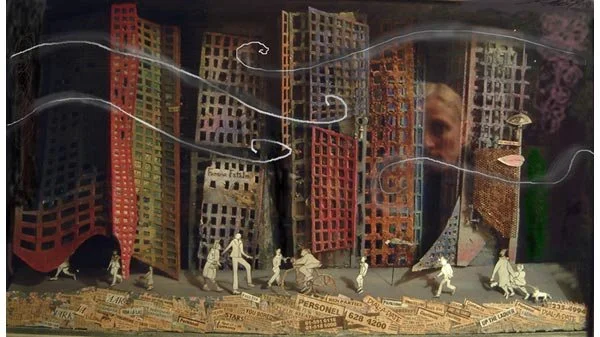

While the characters in these previous films court disapproval through public display of excessive emotion, taking up space and unconventional lifestyle, Susi Jirkuff’s animation installation Where I Live (2022) addresses the expectation that women remain invisible and silent (Elkin 2024, 14). The female protagonist is depicted through her shoes alone: smart, polished footwear, delicately drawn in charcoal lines, denoting a respectability that offers her no protection from indiscriminate bureaucracy. Her passive acceptance of a worsening situation leads to her obliteration, captured in complicit charcoal smears.

All these animated films demonstrate Tricky Women’s ongoing ambition to create a context for the exploration and reinvention of negative female stereotypes. Through modes of transgression, subversion, exaggeration and innovative animation they reimagine the fantasy of the monstrous feminine.

**Article published: October 3, 2025**

References

Creed, Barbara. 1993. The Monstrous-Feminine: Film, Feminism, Psychoanalysis. New York: Routledge

Creed, Barbara. 2022. The Return of the Monstrous-Feminine: Feminist New Wave Cinema. New York: Routledge.

Elkin, Lauren. 2024. Art Monster: Unruly Bodies in Feminist Art. London: Chatto and Windus.

Jackson, Rosemary. 1981. Fantasy: The Literature of Subversion. London: Routledge.

McCormack, Catherine. 2021. Women in the Picture: Women, Art and the Power of Looking London: Icon Books.

Russo, Mary. 1995. The Female Grotesque: Risk, Excess and Modernity. London: Routledge.

Biography

Vicky Smith is an artist film maker and academic who has worked in experimental animation and 16mm film for 35 years and has screened work internationally in galleries and at festivals. Vicky was part of the London Film Makers Co-op and is now a member of artist collective Bristol Experimental Expanded Film (BEEF) in Bristol. She has a PhD in experimental film and lectures in Animation at the University for the Creative Arts, Farnham.