Tracking Reality and Fantasy: how animated music videos play with the persona and non-persona of artists / bands - Part 1

This piece combines the analytical and contextual writing of Shaun Magher and James Clarke with a series of first-person accounts and recollections offered by Magher relating to a series of specific case studies that illustrate the article’s area of exploration.

Across the spectrum of popular music, there’s a fascinating seam that intersects with music, visual culture, and animation. That intersecting seam is the form of the animated music video. These short animations have a rich tradition, and the animated aesthetic can offer a version of a rock/pop star as a fantasy incarnation of themselves.

Over the decades, artists including The Beatles, Peter Gabriel, Radiohead, Pearl Jam, Daft Punk, Michael Jackson, and many others, have utilised animation to enhance or project their identities, blending fantasy, symbolism, and narrative to offer more complex glimpses into the artist's self-image and artistic expression by embracing the animation medium to create new dimensions to their public personae. Music videos have also long offered a significant creative and commercial opportunity for an artist and label. Philip Auslander notes in his chapter Framing Musical Personae that “the music video is in some ways an ideal space for the performance of musical personae because of the greater degree of control over the expressive means that video affords performers” and in many cases artists that utilise animation to promote their new music, enhance their image in a highly targeted way” (2019)

Through social media, fan art, and participation in fan communities, the relationship between the rock star and the audience becomes more interactive, with animation serving as a bridge between the personal and the virtual, the ordinary and the idealised. For Auslander, the “’Persona’ is a flexible term that I (and others) have used in other contexts to suggest a performed role that is somewhere between a person simply behaving as themselves and an actor’s presentation of a fictional character.” (2019)

Most musicians portray themselves when performing and reflect this in their music videos, to centre a sense of reality, integrity and grounding for their audience, and never veer from this norm and never venture into portraying themselves as other. However, many artists do and it is these artists that are much more embracing of the animated medium to develop and enhance their ever-developing persona, such as artists as Ghost, Kiss and many others.

U2 - “Hold Me, Thrill Me, Kiss Me, Kill Me” (1995)

How, then, can the persona or personae of these artists be reimagined, intensified and even challenged through an animated music video presentation? The focus of this piece, and the two blogs that follow, offer up a set of ideas for scrutiny towards that question and in doing so, also invite analysis into the reflections and considerations, and first-hand accounts stemming from Shaun Magher’s work as an animation director on several animated music videos. We explore the relationship between pop star and animator by analysing three animated music videos as case studies: U2’s “Hold Me, Thrill Me, Kiss Me, Kill Me” (1995, ISLAND/WARNER), Holly Johnson’s “Across the Universe” (1991, MCA), and Fluke’s “Atom Bomb” (1996, VIRGIN). Each was directed, or animation directed, by Magher.

Magher himself makes the following critical note: “Ideally, a relationship of trust needs to develop between the Artist and a Director in iterating a narrative and visual style; a process that’s usually driven by a brief treatment written that is then pitched to the Artists, manager and record label. When the process works at its most harmonious, these narrative and aesthetic choices are driven by the Director and embraced by the Artist and herein lies the requirement for trust that is often fragile and that can be easily broken and impact the success or failure of the venture.”

The power dynamic that Magher evokes underscores that a power-dynamic is always present in collaborative partnership. Power asymmetries - whether based on race, class, gender, institutional affiliation, or experience - can significantly impact the fairness and functionality of collaborative endeavours. Ethical collaboration requires an awareness of these dynamics and an intentional effort to counterbalance them. (Garoian and Gaudelius, 2004).

In his work, Magher has always relied upon a simple rule of collaboration, an approach that stemmed from his experience of the animated music-video conception period as he explains: “I have always believed that collaboration is a balance, an agreement, one in which an agreement of creators must exist, otherwise everything falls apart. My simple rule when working with others has always been this – if you cannot agree, abandon the idea, never remain attached and allow it to become a creative blocker for collaboration. We are creative enough to think of something new that will move the idea/project forward”. This principle is echoed by Robert K Sawyer in his Group genius: The creative power of collaboration (2007) where he states that “Directors often enter projects with distinct visual aesthetics, while musicians have conceptual themes tied to lyrics or branding goals. This convergence requires dialogue and compromise.”

In acknowledging the relationship between aesthetic and creative choices and issues of the means of production, it is appropriate to make the point here that deciding to produce an animated music video is not an economical choice, as most animated videos cost more than a standard live-action promo to produce. Setting aside the commercial imperatives, a live-action promo, brimming with visual effects, would be an exception to this situation. For an animation team looking to establish their place in the industry, the production of animated material will present the challenge of reconciling budgetary limitations with potential ambitions to make their mark.

The longer-term intention is for this piece to function as the first step in a larger body of work that will allow additional exploration and reflection on creative practice in the animation industry and consider issues of authorship, genre and narrative. This proposed larger body of work will also evaluate the following question: are directors’ investments in music videos without value? Although fees are paid to directors, most of them work at vastly reduced fees to be allowed to define a new piece of work for their portfolio. Most production companies’ profit margins are miniscule, with the general opinion from artists, their management and labels are that music video directors are privileged to be working with the artist. It’s always a ‘leg up’ to develop their own reputations without any monetary value attached to their investment of time, talent and vision – animators have traditionally had to take a major cut in their fees to work on music videos. The trade-off was always their work would have exposure because of the fame of the artist which attests to the industrial impact of the star; whether pop music star, sport star or movie star.

Magher comments that “On reflection, a key issue that has always been prevalent in the realisation of a narrative and art style aligned to an artist’s vision is establishing a balance between the ways in which different degrees of realism, abstraction and fantasy will either reinforce or re-emphasise the image of an artist or band’s persona. The artist or band are typically looking to avoid misrepresentation to their loyal audiences. This process is about aligning to an artist’s trust in a director to not damage their brand.”

Hold Me, Thrill Me, Kiss Me, Kill Me

Discussing his first-hand involvement in the animation production of the U2 music video for “Hold Me, Thrill Me, Kiss Me, Kill Me,” Magher remembers that:

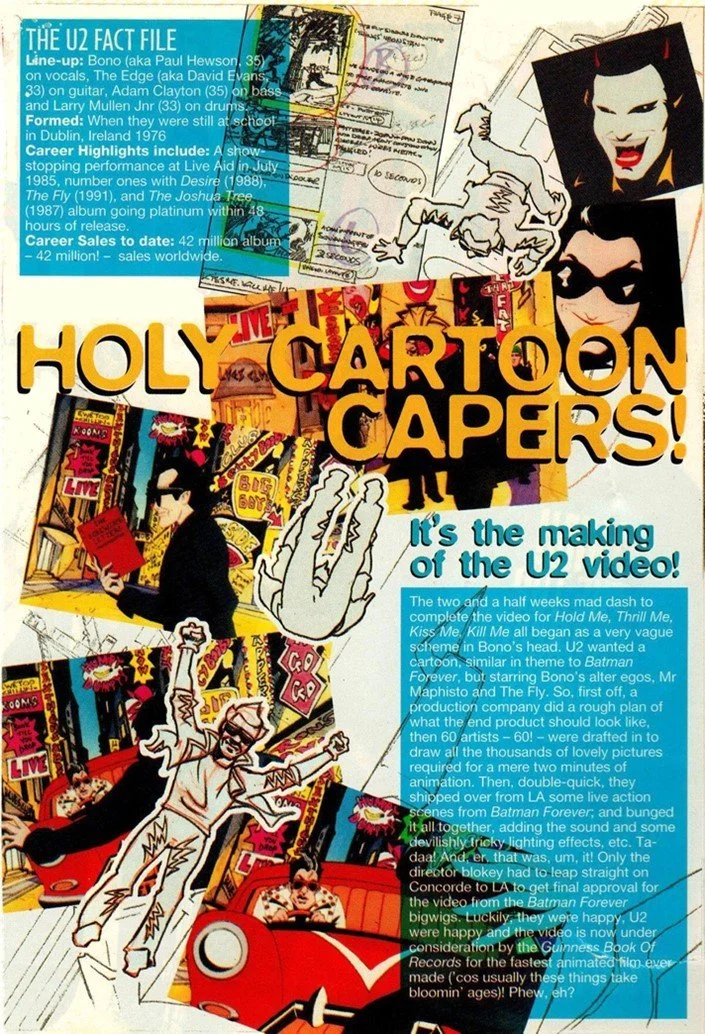

“In 1995, U2 loaned one of their Zooropa tracks, “Hold Me, Thrill Me, Kiss Me, Kill Me,” to the film Batman Forever (Joel Schumacher, 1995). Both Bono and Schumacher tried to develop one of Bono’s alter-egos, McPhisto, into a cameo for Batman Forever, but alas timings and conflicts in schedules would not allow the cameo to happen. As an alternative arrangement, U2 instead agreed to allow Schumacher the use of the track for the closing titles of the film. This soon became an ideal opportunity for Bono to use the music video format to experiment with his various personae. In an interview in 1996, with Juice magazine, Bono stated “what we did with ZooTV was a way of stopping me being placed as one person, because you have to accept the caricaturing that goes when you become a big band, have fun with it and create these alter egos”. Bono had developed McPhisto (based on Mephistopheles) to parody the Devil and The Rockstar, to explore self-satire and general social trappings, and quite blatantly jettisoning previous U2 era themes. The Fly is an amalgam of two of Bono’s biggest musical influences, Elvis and Jim Morrison, both of whom came to a tragic demise. Bono was fascinated with reinventing his image, but each persona projected symbolic messages, particularly about overstaying his time in each is a way to deal with mega fame, as is emphasised within the song’s lyrics as essentially the song’s theme is being imprisoned within a persona that he cannot escape and if the inner self can survive. The title of the song is a metaphor of the trappings of fame and the inevitable consumption by it, something Bono was keen to portray within the video and saw an ideal parallel with Batman and his own masks and essentially to navigate the dichotomy between public adulation and personal authenticity.”

The video was originally planned by Maurice Linnane (Dreamchaser Productions), who was responsible for the onstage tour videos for ZooTV. However, the role of Director was passed to Kevin Godley, but not before the production had started by the animation teams at Manga Studios, led by Magher. Perhaps it’s no surprise to make the point that different performers yield different aesthetic approaches to how they are represented within animated characters. Reflecting on the project, Magher notes that it was the case that there was a dynamic evidently at work in terms of who was authoring the collaborative work of the music video.

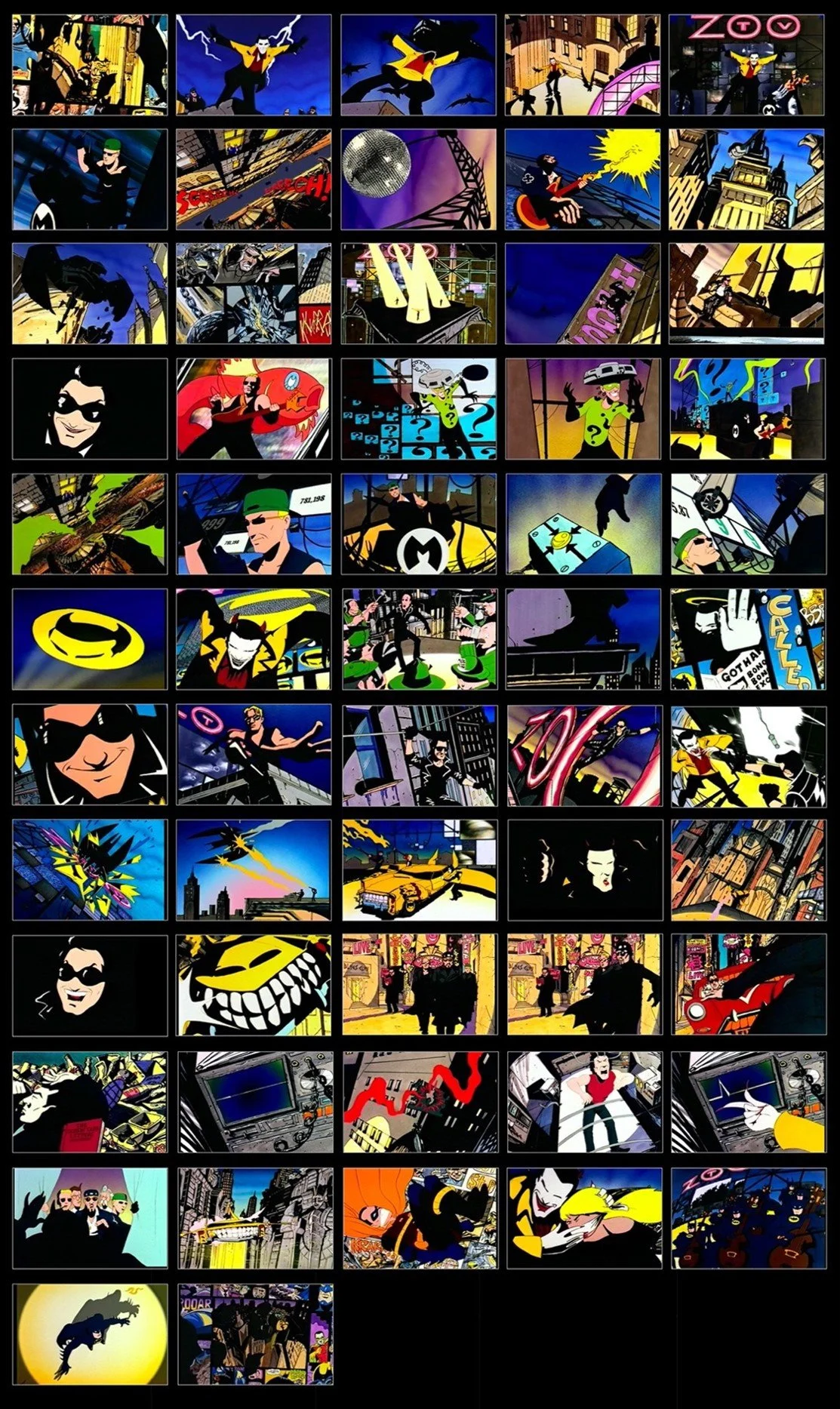

Magher continues with his recollection and reflections on aesthetic choices for the video: “With a team of over seventy animators and artists at work, the video was made over an 11-day period. The focus of our work at Manga Studios was to build a style that would be reminiscent of Frank Miller’s Dark Knight and would feature Bono’s McPhisto as the main antagonist and his other persona, The Fly, as the protagonist. It was an obvious amalgam, to bring a classic comic-feel to the video, that allowed a strong and long-established iconic set of characters and a narrative fusing the duality within a superhero, aligned to the personal battle of Bono’s own balance between public portrayal and projecting his numerous alter-egos”.

According to scholar Neal Curtis, this relationship between superheroes and myths, allows “superheroes function as modern myths that reflect societal values and struggles… This perspective highlights how superhero narratives serve as a mirror to contemporary cultural issues” (2019). The dual identity of superheroes was vividly explored in the classic Frank Miller-authored Batman comic series. As Miller noted in an interview with Heritage Auctions in 2023: “I was finding my way, and I found myself, more and more, looking to recreate the blocky, chunky, Father-figure Batman that I’d grown up with, drawn by Dick Sprang on the 1950’s, because I didn’t want Batman to become a fantasy of what I wanted it to be” (2023).

Critically, the Batman shape-language evolved through Miller’s work from a thinner, elongated character to the iconic rugged, more imposing Batman towards the end of the series. It was decided by Magher and the Art Direction team to find a middle ground, to define a fusion of Miller and the characters from the Joel Schumacher movie.

Magher offers up a further set of observations about his experience of the aesthetic and narrative approaches deployed in the U2 music video: “As with the narrative thread that’s typical in the superhero comic genre, duality rears its head. The timeline in “Hold Me, Thrill Me, Kiss Me, Kill Me” is nonlinear, and it establishes the McPhisto character early on, cheating the audience into thinking that they are viewing Batman atop a skyscraper. We then reveal that it is McPhisto performing with the band, lighting illuminated the bat silhouette, to reveal his glistening golden jacket and red horns. He has serious intentions, with his convertible, winged gold Cadillac. The two Bono alter-egos run in parallel throughout the video. However, there is a fleeting meeting between the Fly and McPhisto. The Fly, who has been harassed by Paparazzi, and forced to the edge of a precipice, falls off a building, only to find himself being caught by a wire and then slides down a building. He then meets McPhisto climbing up the building on a gargoyle and the characters’ eyes meet.

The design of the piece was economical, relying on defining the upper body of characters in full light and the base of characters in silhouette. This of course a requirement, to limit ‘line mileage’ and to help define key characteristics without being overwhelmed with detail, a necessity when planning traditional drawn animation”.

The video brims with multiple levels of symbolism that resonate with U2’s history: The Dead Elvis character who runs over Bono in an alley way whilst he is reading a copy of C.S. Lewis’s The Screwtape Letters, is a metaphor for stardom excess, the pursuit of fame and the demands that makes on an individual. It is very much a symbol of the ultimate price of fame and being hounded by paparazzi. The Screwtape Letters, a series of letters from a senior demon to his apprentice about tempting humans, resonates with Bono’s McPhisto character, who embodies seductive power.

Magher recalls that “The bar in the scene was originally called Mr Pussy’s, the name of a bar Bono and his brother ran; but the name didn’t get past the MTV censors and was changed to Mr Swampey’s, named after Kevin Godley’s three-legged dog. I had a frantic phone call from Kevin at 4am in the morning (the studio was working 24 hours to chase the deadline) and he was extremely upset as his dog had died. I was on the phone to Kevin for hours. As a result of that, the name of Mr Swampey was used as the new name for the bar and was added by Ned O’Hanlon, when the production was forced by MTV to make its last-minute edit in New York before the video was premiered.”

The observation that Magher makes here about the improvised and ‘unplanned’ adjustments that are typically made to story-points is characteristic of collaboration, and certainly became part of his experience of working with creative choices in his collaboration with Holly Johnson for the music video for the song Across the Universe, which will be explored in next week’s second part.

**Article published: October 17, 2025**

References

Auslander, Philip, 2019. “Framing Musical Personae.” In The Bloomsbury Handbook of Popular Music Video Analysis, edited by Lori A. Burns and Stan Hawkins, 91–110. London: Bloomsbury.

Curtis, Neal, 2019. “Superheroes and the mythic imagination: Order, Agency and Politics.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 12. no. 5: 360–374.

Garoian, C. R., and Y.M. Gaudelius, 2004. “The Spectacle of Visual Culture.” Studies in Art Education 45, 4: 298–312.

Frank Miller Heritage Auctions, 2023.

Mountfort, Paul. 2020. “Tintin, gender and desire.” Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics 12, no. 5: 630–646.

Reynolds, Simon, 1998. Energy Flash: A Journey Through Rave Music and Dance Culture. London: Faber & Faber.

Sawyer, Keith. 2007. Group Genius: The Creative Power of Collaboration. New York: Basic Books.

Shaviro, Steven, 2003. Connected, or What It Means to Live in the Network Society. Minneapolis: Minnesota Press.

Westrup, Laurel, 2023. “Music Video, Remediation, and Generic Recombination.” Television & New Media 24, no. 5: 571–583.

Biography

Shaun Magher is Course Director BA (Hons) Digital Animation, MA Feature Film Development, and the Lead on the MA Film Academy at Birmingham City University Follow Shaun on Instagram at: https://www.instagram.com/shaunmagher/

James Clarke is a writer, script reader and educator in HE. He has contributed as a Visiting Lecturer to the MA Feature Film Development course at Birmingham City University. He has also taught on the MA Screenwriting course at London Film School and currently teaches on MA Writing for Script and Screen online course for Falmouth University. Follow James on Instagram at @Jameswriter72.