Fantastic Turkish Cinema: Re-make or Not Re-make, That’s the Question - Part 2

In the previous blog post, I introduced a couple of eccentric films that have since been celebrated as cult classics. Rumour has it that The Man Who Saves the World, mentioned in that post, has been selected as one of the ten worst films ever made and is taught at universities in the US as an example of how not to make a film.[1] Discussing these productions, I aimed to underline the do-it-yourself ethos of the era, the constraints of the industry, and the creative solutions filmmakers came up with to these limitations, even sometimes at the risk of making absurd films. In this second part, I will unveil an even more striking and amusing film, further showcasing the chaotic yet uniquely captivating approach of Yeşilçam cinema.

Marvel fans yearned for years to watch the mentor-student-like relationship between Captain America and Spiderman on the big screen, but it didn’t happen until 2016 with the release of Captain America: Civil War due to the rights of those heroes belonging to different studios. However, if you believe that’s the case, you’re mistaken. The two characters indeed starred together, along with a wrestler hero called El Santo from Mexican comics (the connection remains a mystery), in a Turkish film called 3 Giant Men (3 Dev Adam), directed by T. Fikret Uçak in 1973. And believe me when I say, even Dr. Strange, while looking at 14 million alternate futures in Infinity War, wouldn't have imagined this story…

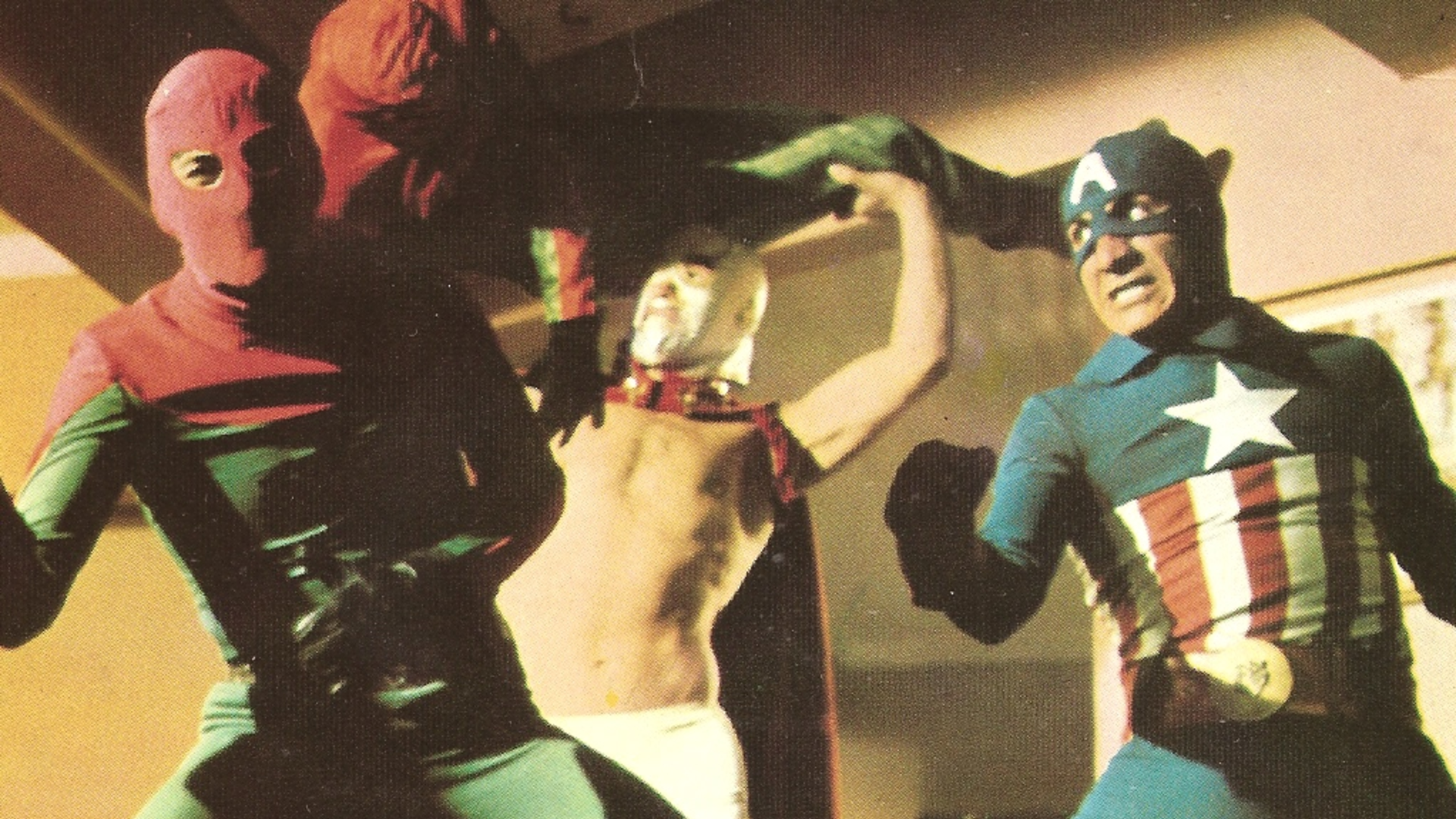

The governments of the US and Mexico send their superheroes, Captain America (Aytekin Akkaya) and Santo (Yavuz Selekman) respectively, to assist Turkish police in busting a gang involved in smuggling historical artifacts, led by Spiderman (Tevfik Şen). Interestingly, instead of the film portraying the friendly, wholesome character we are accustomed to, Spiderman is depicted as a bloodthirsty villain. 3 Giant Men also stands out from other movies mentioned in this article (and in Part I) due to its inclusion of blood, torture, and notably erotic scenes. For instance, Spiderman gruesomely dismembers a woman’s face with the motor of a small boat while her body is buried in sand; he forces a mouse to eat the eyes of a man who betrayed him; and impales a couple during an intimate moment. At times, Captain America and Santo manage to corner Spiderman, but unexpectedly, a new gang of Spidermen appears. With this, I believe the producers intended to link him better to being Spiderman, or at least suggest an insect-like nature; given that the Turkish Spiderman neither climbs walls, throws webs, nor possesses superhuman strength. Ultimately, the mighty heroes—again, without any superpowers, as that would require special effects, of course—defeat the Spidermen using sheer strength and a bit of awkwardness, save the artifacts, and return to their respective countries (Fig. 1).

Giovanni Scognamillo and Metin Demirhan in their book Fantastic Turkish Cinema, quote the American author Keith T. Breese, who was unable to hide his astonishment after somehow coming across this Turkish cult film on a VHS tape:

‘‘It is a Turkish film that needs to be watched to be truly understood. Believe it or not, this is not satire. It is a serious film that tackles superheroes and supervillains. Of course, it was shot in a messy, cheap, and poor manner, but it is for sure one of a kind’’ (Breese as quoted in Scognamillo & Demirhan 1999, 242).

What better way, then, to epitomize the essence of Yeşilçam—messy yet sincere in its execution, a testament to the profound creativity that captivates us all in cinema? Through these films, Yeşilçam embraced its chaotic and creative spirit by delving into the fantasy. After all, is it not the fantasy genre, with its leviathan imagination and charm—the very stuff dreams are made of—that perfectly sums up the spirit of Yeşilçam’s filmmaking?

As I mentioned in Part I, facing financial limitations and tight schedules, filmmakers turned to borrowing from foreign films because it was quicker to adapt an existing film; and not surprisingly, they had to rush the production of their films too. For instance, Çetin İnanç is known for shooting a feature superhero film (Bombala Oski Bombala, 1972) in just one day and completing the editing the next. Even though fantasy was not one of the most prevailing genres in Yeşilçam, it is notable that some filmmakers always harbored a love for exploring these narratives (Fig. 2). İnanç, being one of them, attributes his passion to the impact the American productions he watched in his youth had on him, and continues by saying: ‘‘Our childhood was so wonderful. No matter one’s age, one shouldn’t forget their childhood. That’s why I made those films.’’ (Scognamillo & Demirhan 1999, 366).

All these examples, and many more that I neither have the space nor the scope to mention here, were created with extremely restricted resources and limited time. This is, in fact, the result of a long and complicated economic period. Nevertheless, Yeşilçam was able to persevere by leveraging these tales, superheroes, and characters, reaching to a wide audience, even if it sometimes meant producing lowbrow content. When discussing 3 Giant Men in his book Hollywood Meme: Transnational Adaptations in World Cinema, Iain Robert Smith notes: ‘‘We saw how the borrowing of the characters Captain America, Santo the wrestler, and Spider-Man helped draw attention to a relatively generic crime film within an economic market that did not allow for large marketing budgets or expensive promotion strategies.’’(Smith 2017, 73). Indeed, Turkish cinema was in search of borrowing from foreign productions. In a market constrained by modest marketing budgets and limited cinematic resources, the underdeveloped film industry, hindered by economic and technological limitations, was unable to produce its own original narratives. It must be acknowledged that the Turkish audience of the ‘60s and ‘70s, despite being somewhat familiar with Hollywood films, naturally gravitated towards those with motifs and plots connected to their homeland. Watching Cüneyt Arkin saving the world on another planet or seeing Aytekin Akkaya in a Captain America costume, though potentially amusing and exaggerated, was decidedly more accessible for Turkish audiences to identify and connect with.

Studying these films in the 21st century might seem nostalgic, but I hope for it to be more than just that—a reflection and perhaps a glimpse of aesthetic insight, aiming to shed light on the spirit of a country’s cinema. As can be seen, cinema can be many things. Viewed from this perspective, the Turkish cinema explored here, which emerged under extremely challenging conditions and is set in fictional universes (but visually very close to ours because of the lack of production and special effects), inspired by Western productions but enriched with local folkloric, cultural, and metaphysical elements; can indeed be considered fantastic. In the end, creating a cult film doesn’t necessarily require the imagination of Jim Henson, the whimsy of Terry Gilliam, or the surrealism of David Lynch. It merely takes a willingness to spurn the rules, deform the form, and while working under extreme difficulties, to recreate cinema with its primal simplicity. Thus, it becomes a spectacle that transports people away from their mundane world for a couple of hours and introduces them to fantastic realities, one way or another. Bringing our journey through the fantastic realms of Turkish cinema to a close, I echo the words of Scognamillo and Demirhan: ‘‘After all, who can remain unchanged after watching The Man Who Saves the World?’’

**Article published: April 12, 2024**

Notes

[1] Although I couldn’t find any official sources to confirm these claims, they were posed to the film’s director Çetin İnanç at one point, and he responded: ‘‘I haven’t received a document on this. I believe they are just rumors. Either way, they bring attention to the film, they work in its favor’’ (Scognamillo & Demirhan 1999, 371).

References

Scognamillo, Giovanni, Metin Demirhan. 1999. Fantastik Türk Sineması. Istanbul: Kabalcı Yayınevi.

Smith, Iain Robert, 2017. The Hollywood Meme: Transnational Adaptations in World Cinema. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Biography

Hailing from Istanbul but now soaking up the Los Angeles sun, Sedef has donned many hats—both literally and metaphorically—from creative director to filmmaker. Yet, her true love has always been film criticism. This passion led her from Film & TV studies in Istanbul to a master’s in Film Studies at King's College London, all on a full scholarship thanks to her academic achievements. Nowadays, she oversees content for an arts magazine, penning and editing pieces for the cinema section, while also globe-trotting to film festivals.