Fantastic Turkish Cinema: Re-make or Not Re-make, That’s the Question - Part I

Believe it or not, Yeşilçam, the studio system of Turkey, which became dominant from the 1960s to the 1980s, essentially introduced classical cinema to Turks. It drew its production systems from Hollywood—big producers familiarized themselves with the studio structure in Los Angeles and brought the same system back home—but localized the content to reflect the specific experiences of Turkish society. That said, industrial concerns were not the only concepts borrowed from the edge of Western civilization. Blockbusters such as Star Wars, Superman, and Spiderman were also remade by Turkish filmmakers, especially during the ‘70s and ‘80s. During that time, Yeşilçam was known for its limited resources, and so produced these films unlicensed with makeshift effects that indeed appeared ‘homemade.’ With the help of lenient copyright laws, this era, humorously dubbed Turksploitation, led to the production of low-budget films that reused content from popular foreign movies while localizing plots and characters to better connect with the audiences in Turkey. Now, as someone who was born and raised in Istanbul, where Yeşilçam itself was born and flourished, I look back at those films with mixed feelings. I am torn between viewing them as examples of nostalgia and ingenuity in cinema, while also can’t help seeing them as embarrassing rip-offs. Nevertheless, the charm of these films as I argue in this blog post often lies in their imperfections. By venturing into the fantasy genre and employing unconventional special effects to bring their imaginative worlds to life, they lay bare the creativity born out of necessity; which perhaps works as a testament to cinema's broader power in adapting, interpreting, and telling stories under the most restrictive conditions.

Taking its name from the street in Istanbul, where many actors, directors, and studios were based, Yeşilçam was like a breath of fresh air for the cinema-hungry audience in Turkey of the 1960s. Not without its constraints, of course, and with the lack of funds it was bound to extra-sectoral loans. It therefore should not come as a surprise that the whole industry was formed with the sole purpose of making money. As expected, this led to compromises in cinematic artistry, and as if that was not challenging enough, in the seventies cinema also had to compete with TV. In short, Yeşilçam was put together homemade, with its primary focus on avoiding risks. Just like Hollywood, they made yearly production plans and worked with stars to ensure success. Unlike Hollywood, however, it was far from a big industry protected by subsidies and with extreme specializations. Although Yeşilçam emulated Hollywood, it was merely a sector, which made films substantially in debt. It had a do-it-yourself ethos and tendency to advance with imitations since the system in which filmmakers worked offered commercial guarantees. Soon these tactics proved lucrative, and subsequently, the production volume increased incrementally. In 1965, over 200 films were produced in Yeşilçam (Kirel 2005, 41).

At this point, adaptations of Western cinema became even more prominent, primarily because of their financial appeal, but also because it was easier and quicker to (re)produce narratives and characters from an existing film. However, don't just take my word for it; consider the perspective of Nusret İkbal, a well-known producer of the era:

The number of our original films wouldn’t be more than three or five. Because, along with their plots, we steal foreign films’ images, gimmicks, even their scenes. After snatching them as we wish, we call it ‘‘inspiration’’. As a matter of fact, it is sheer sleight of hand. However, anyone producing 150 films a year is inevitably going to steal. Given the rapid pace of Yeşilçam, no filmmaker could truly create something from scratch because neither the time nor the creativity would suffice (Scognamillo 1973, 67).

It's important to note that the genres of the films mentioned in this post were not the only ones adapted by Yeşilçam filmmakers. Over the years, a wide range of movies, from Some Like It Hot to The Adventures of Robin Hood, were adapted and presented to suit the tastes of Turkish audiences. However, apart from the fact that this blog is titled Fantasy/Animation, these particular renditions of big screen fantasy capture my interest the most. Thus, I will now concentrate in this blog (and in next week’s Part II) on specific examples within the fantasy and sci-fi genres moving forward.

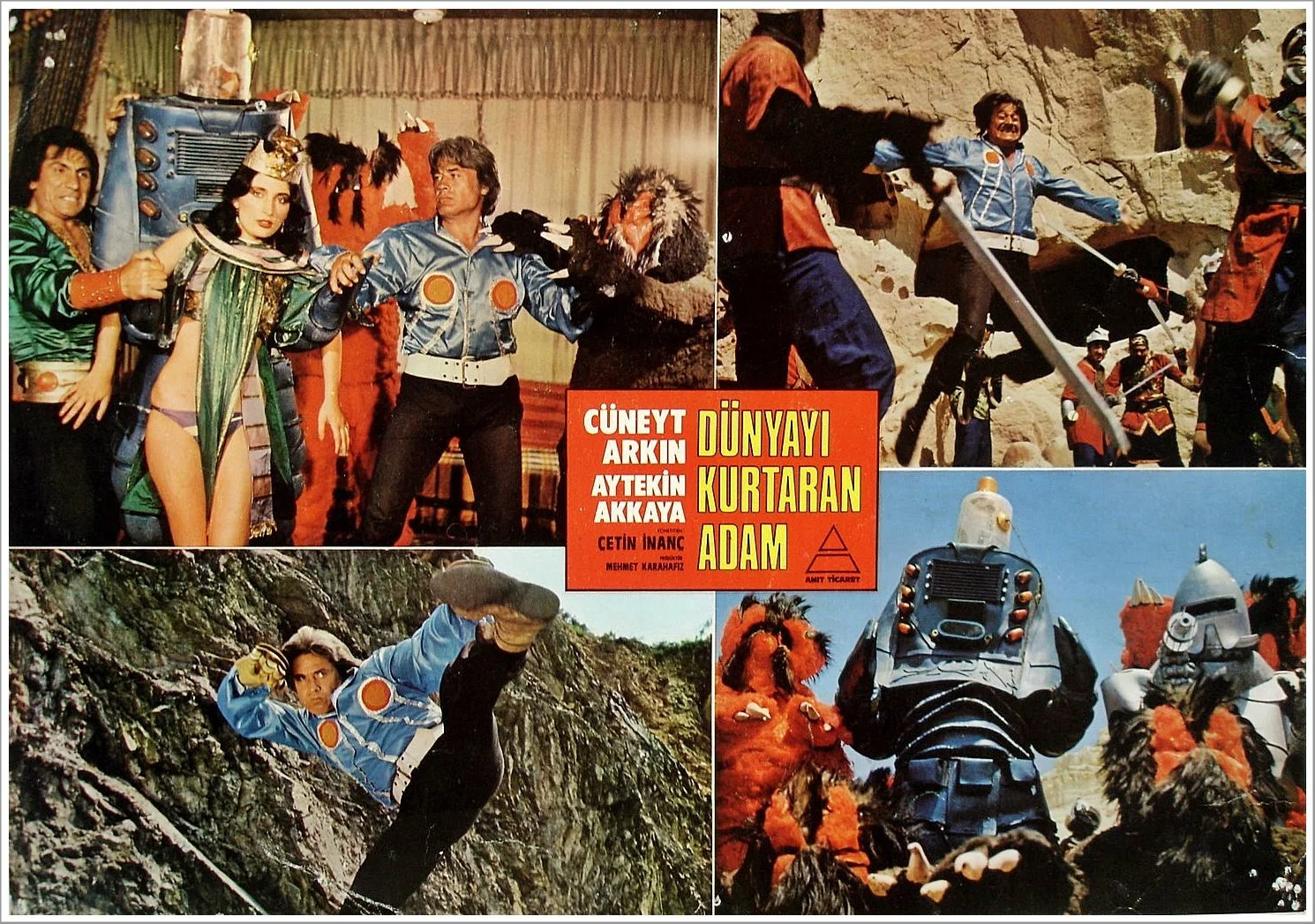

The first example that comes to mind is none other than the (in)famous Turkish Star Wars, known as Dünyayı Kurtaran Adam (1982), which literally translates as The Man Who Saves the World—a film now celebrated as a cult classic. Directed by Çetin İnanç, nicknamed the ‘‘Jet Director’’ for his swift filmmaking pace and with over 150 movies to his name; The Man Who Saves the World was initially introduced as a costume piece. It can be classified as science fiction and perhaps a space opera, making it a unique example of the genre in Turkish cinema, especially considering such genres were, and perhaps still are, uncommonly produced in the country's film industry (Figs. 1 and 2). The protagonists of the film, two Turkish astronauts (Cüneyt Arkin and Aytekin Akkaya), crash on an unknown planet while wandering through space. Viewers might find the first ten minutes especially familiar, given the jauntily lifted scenes from the original Star Wars, including unauthorized footage of space battles, starfighters, and even the Death Star. However, the rest of the film seems otherworldly, after all, who can prepare themselves to watch heroes who ride horses in space?

On this foreign planet, filled with familiar terrestrial sights, we see horsemen and subsequently monsters with masks, clearly made of cardboard and plastic. As the film unfolds, we learn the secrets of this planet from a masked man called the Magician. It turns out he is trying to capture the world, as he needs the most powerful thing in the galaxy: the human brain. While fighting the Magician, the heroes, not having special effects at their disposal—and therefore not the Force—resort to brute force. Cüneyt Arkin beats up rocks, smashing them with his punches. The alien warriors, on the other hand, respond with cardboard swords, rather than lightsabers, wearing ridiculous costumes that appear to be cobbled together from various materials such as fur, plastic, and everyday items. In one scene, the old wise man of the planet takes Cüneyt Arkin to a shrine and explains the importance of the Islam—likely because Jedi principles wouldn't resonate with the Turkish audience.

As a mastermind of localization, The Man Who Saves the World blends martial arts and metaphysical elements with cultural and folkloric references, offering an identifiable fantasy narrative to its audience. Bearing in mind the film’s self-spoiling title, Cüneyt Arkin ultimately defeats the Magician and therefore saves the world, before returning home riding the Millennium Falcon (Fig. 3).

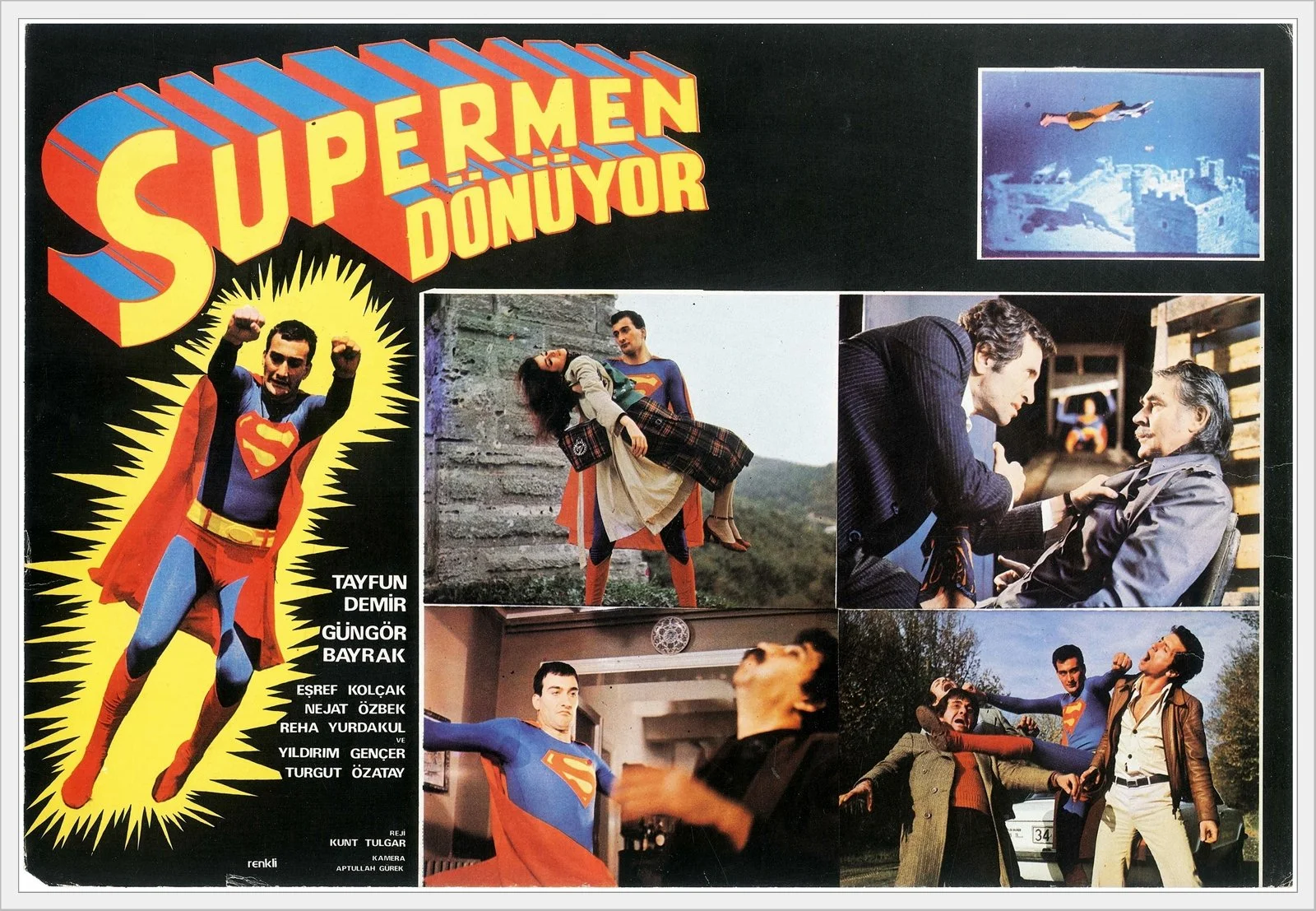

Superman was another franchise that Turkish producers were keen to draw inspiration from. In fact, the superhero craze that started in 1967 saw Yeşilçam tapping into American comics and serials of the ‘40s and ‘50s (Scognamillo & Demirhan 1999, 13). Thus, while Hollywood was busy reimagining Superman in 1978, Turkish cinema had already debuted the iconic character on the big screen in 1969. While several Superman-inspired films were produced during the Yeşilçam era, one standout example that did not refrain from adding its own diversifications to the famous franchise was Superman Returns (Süpermen Dönüyor, 1979) directed by Kunt Tulgar (Fig. 4).

Starting with a plot highly similar to the original story, Tayfun (Tayfun Demir) decides to become a journalist after finishing college. Around that time, he also discovers he is adopted and that his parents found him in a rocket, accompanied by a green stone. Guided by telepathic voices from the stone, he is led to a dust cloud where he encounters a man who claims to be the lord of Krypton and his father; stating that Tayfun possesses ‘‘the wisdom of Solomon, the strength of Hercules, the stamina of Atlas, the power of Zeus, the courage of Achilles, and the speed of Mercury’’. This description mirrors the verbatim formula for Shazam’s powers, another character within the DC Universe. The film’s scriptwriter, Emel Tulgar, must be a significant DC fan, incorporating elements not just from one source but from various comics, also introducing this famous mantra for the first time on the silver screen. It's worth noting that, to date, there has not been an American live-action film where Shazam and Superman team up or interact, aside from a very brief cameo in Shazam! (Sandberg, 2019).

The rest is the classic story: Superman fights against villains who want to capture the green stone, flying over famous landmarks of Istanbul with more grounded, albeit inventive visual effects achieved through rudimentary back-projection and creative camera work. Naturally, he falls for his newspaper colleague Alev (Güngör Bayrak), who adores Superman but overlooks Tayfun, unable to recognize him behind his glasses. Ultimately, Superman defeats the villains and Alev finds out that Superman is in fact, Tayfun. She urges him to stay, however, choosing to seek his life’s purpose, he opts to leave Earth. In contrast to The Man Who Saves the World, this time the film’s title, Superman Returns, instead of spoiling it, throws an unexpected curveball, as Superman leaves for good.

As I mentioned at the beginning, although the primary concern in Yeşilçam was to make money, these films were not made solely for commercial purposes. They also hoped to offer their audience tidbits that had not existed before in their own language and culture. These films captivated a specific audience—primarily kids and young adults—presenting them with new images and infused new life into the conventional narratives of Yeşilçam. Setting all else aside, in a country 7,000 miles away from Hollywood, in a brand new film industry fraught with challenges, the choice to remake films like Star Wars and dive into the realms of superhero comics speaks volumes about the universal appeal of the fantasy genre. Of course, the limited resources led to unexpected innovations; and if you thought the borrowing of actual footage from Star Wars was amusing, bear in mind that this is an industry in which filmmakers produced several Western films without being able to cast a single horse.

Rest assured, unlike the Turkish Superman, this article will return with its second part soon.

**Article published: April 5, 2024**

References

Kirel, Serpil. 2005. Yeşilçam Öykü Sineması. Istanbul: Babil Yayınları.

Scognamillo, Giovanni, and Metin Demirhan. 1999. Fantastik Türk Sineması. Istanbul: Kabalcı Yayınevi.

Scognamillo, Giovanni. 1973. ‘‘Türk Sinemasında Yabancı Uyarlamalar’’. Yedinci Sanat, vol. 9: 61.

Biography

Hailing from Istanbul but now soaking up the Los Angeles sun, Sedef has donned many hats—both literally and metaphorically—from creative director to filmmaker. Yet, her true love has always been film criticism. This passion led her from Film & TV studies in Istanbul to a master’s in Film Studies at King's College London, all on a full scholarship thanks to her academic achievements. Nowadays, she oversees content for an arts magazine, penning and editing pieces for the cinema section, while also globe-trotting to film festivals.