“Two Cadaverous Vultures”: Disney’s Gift to the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York

In January 1939, the Metropolitan Museum of Art announced its acceptance of an animation cel set-up from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs (David Hand, 1937) and “presented by the artist, Walt Disney” (Burroughs, 1939) (Fig. 1). The gift — an ink and gouache painting on transparent celluloid, laid over a hand-painted background — was duly hung with the museum’s other “recent accessions,” and immediately generated considerable coverage in the nation’s major newspapers, magazines, and wire services (e.g. Anon., 1939b., 42; Associated Press, 1939c, 2; Anon., 1939c, 20; Anon., 1939d, 17; Associated Press, 1939b, 4; Associated Press, 1939a, 6; Nugent, 1939, 4-5). New York art dealer, Julien Levy, acted as the middleman delivering the cel to the Met in November 1938 on behalf of Disney and Levy’s personal friend, Guthrie Courvoisier (1903-66), owner of Courvoisier Galleries in San Francisco (Kent, 1938; Burchard, 2021, 17). At the time, Courvoisier held exclusive distribution rights for Disney art, thanks to a deal struck with Walt and Roy Disney the previous July (Munsey, 1974, 186). The gift, which marked a high point in the critical fortunes of Walt and his studio in the late 1930s, prompted senior Met curator Harry B. Wehle to famously declare Walt “a great historical figure in the development of American art” (Associated Press, 1939c, 2).

In the Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin for February 1939, the image was described as depicting, “perched ominously on a bough in the driving rain, the two black vultures which in the film bear such awesome witness to the fall of the wicked queen” (Burroughs, 1939). The unusual subject sparked almost immediate comment. “Vultures of all things are the only creatures in the picture,” the Associated Press reported. “Explaining why a scene with the title characters was not chosen,” the AP declared, “officials at the museum said, in their opinion, Disney shows ‘a better understanding’ of animals than human beings” (Associated Press, 1939c, 2). A photo of the cel set-up appeared in the February 6, 1939 issue of Time magazine. In an adjoining article entitled “Grim Disney” Time informed its vast readership that “many who saw the picture were surprised by the Metropolitan’s choice.” The piece continued, “Not Mickey Mouse, not the foolish pigs, not Donald Duck in a snit, not the awkward Goof nor Horace the hopeless horse, not Dopey, no wide-eyed tender creature of the field or wood was chosen. The choice: a scene from Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs…(of) two cadaverous vultures…” (1939b, 42).

Despite widespread “surprise” in 1939, among the few scholars who have since made mention of the gift, not one has addressed the question of the Vultures’ significance as the central motif in a museum-worthy work of art (Watts, 124; Apgar, 2015, 213-14; Neuman, 1999, 250-51; Kaufman, 2012, 249; Burchard, 2021, 17-18). Recently, however, Garry Apgar has proposed one possible explanation. The gift he says, may represent “a sly dig” on Walt’s part “at the myriad of Hosannas then being heaped on him” in the art world. In other words, Walt may have selected the cel as “an inside joke — a visual play on the term ‘culture vulture,’ which by the 1920s had entered the language” (Apgar, 2023). Although contemporary news stories used the word “choice,” no hard evidence has yet surfaced to indicate the museum had a choice. In his 2021 discussion of The Vultures Met curator, Wolf Burchard, states that “Walt Disney presented The Met” with the cel, suggesting that it was Disney’s personal pick — and the only one on offer, as well — as Apgar also implies (Burchard, 17). Nonetheless, one can’t help but wonder if it was Disney who actually made the selection?

Several letters exchanged by Courvoisier with one of his most successful independent dealers, Hollywood socialite Edith Wakeman Hughes (1876-1957), suggests otherwise (Holian, 2023). This unpublished correspondence reveals new information about The Vultures and hints at possible answers to the “who” and the “why” of the Disney gift. On February 9, 1939, Courvoisier wrote Hughes in response, apparently, to her expressed interest in marketing versions of The Vultures. Courvoisier told Hughes that “there were only two Vultures made up, one the small set-up which I am including, and also the large (format) celluloid which was reproduced in Time Magazine (and)…on exhibition in the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York” (Courvoisier, 1939b).[1]

Courvoisier’s phrase — “made up” — references the work of the “newly formed” Cel Setup Department at the Disney studio, composed of employees from the Ink and Paint Department, who prepared animation artwork for sale (Johnson, 2017, 144). The smaller cels probably measured five by five and a half inches and consisted of two vultures cut from their celluloid sheet, and affixed to a specially made wood veneer background [2]; Backgrounds of this type were common for trimmed Disney cels (Fig. 2). In contrast, the Met’s work measures a little over ten by nine inches with two layers of celluloid (Burchard, 213), one bearing the Vultures and the other slicing, abstract raindrops. The celluloid sheets lay atop a gouache and watercolor post-production background also prepared by the Cel Setup Department. When Courvoisier received a batch of cels from the same sequence the entire group bore the same inventory number despite each image being slightly different. The Met’s piece was identified as “Vultures #81” in Courvoisier’s correspondence and inventories, where it was priced at $30, making it one of the more expensive pieces within the standard $5 to $35 price range Courvoisier used (Hixon, 1939; Anon., 1939a, 2). The numbering and original price of the smaller Vultures, like the one sent to Hughes, are presently unknown.

As he often did in his letters, Courvoisier then informs Hughes about the importance and relative rarity of the works he planned to send her. In this case, he noted that the “small Vultures” is the “only one left as far as I know. This particular cell [sic] has been considered one of the finest by art critics and museum people” (Courvoisier, 1939b). Given this ringing endorsement of the smaller set-up, it’s reasonable to assume that the larger, more “complete” Vultures was even more highly prized by the cognoscenti, suggesting why the unusual subject matter was chosen for the Met.

Walt, or his brother Roy almost certainly approved the gift, but entrusted the final choice to Courvoisier, who was probably guided by art critic, Dorothy Grafly, a contributing editor with Art Digest, whose effusive views on Snow White were well known; Since the start of the Disney enterprise, Courvoisier had relied upon Grafly’s remarks to help sell the feature’s production art (Courvoisier, 1938a, 1938b, 1939a). Indeed, in her critique of the film, Grafly specifically singled out a handful of elements as examples of Snow White’s “artistry;” The vultures are referenced twice in the review. (Anon., 1938, 25).

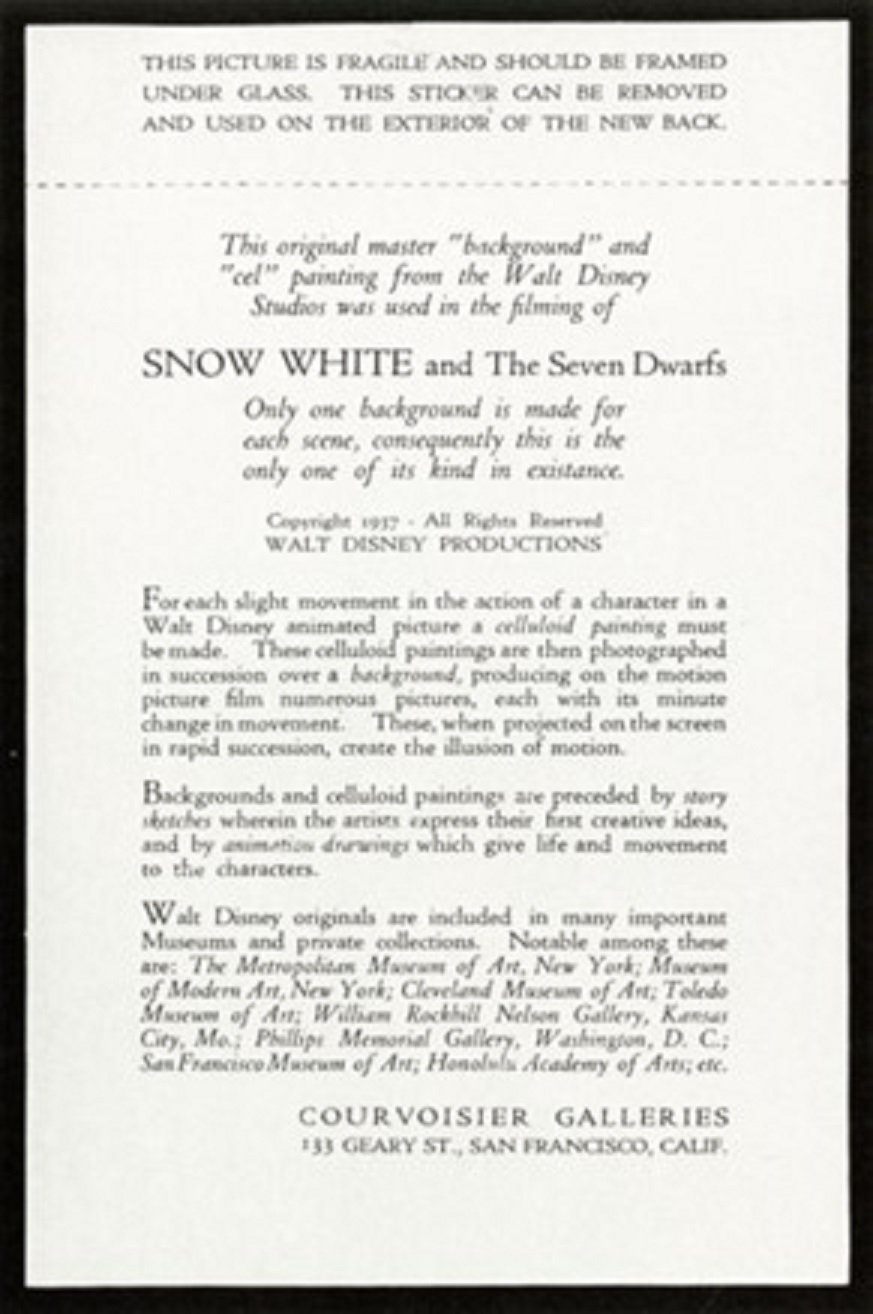

Not surprisingly, after the highly publicized gift entered the Met, “Vultures #81” was in high demand among collectors, and within a year, the last one was apparently sold to Hughes client, Alex Tiers, in December 1939 (Hughes 1939b). In her final shipment memo to Tiers she prophetically encourages him to keep the piece for himself, “as I feel it will be so valuable some day” (1939a). In the wake of the museum’s acceptance of the cel, the shrewd Courvoisier did everything he could to take advantage of the publicity, as well as the increased prestige and value all Disney-Courvoisier works enjoyed as a result. He began affixing an official gallery label to the back of each Disney work that listed US museums holding at least one of the studio’s pieces. At the top of the list was the Metropolitan Museum of Art (Fig. 3).

The Vultures has been exhibited just once at the Met since 1939 (Anon. n.d.) but its warm embrace by the most prestigious museum in the country conferred elite “fine art” status on it and Disney animation art more generally—which, as I’ve argued elsewhere—changed the way it was literally and metaphorically viewed and, in some cases, displayed (Holian, 2022). Much of the credit for this important shift lies with the bold and informed judgment of Guthrie Courvoisier.

**Article published: March 1, 2024**

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Garry Apgar for generously sharing his unpublished work. His feedback during the editing of this piece was likewise invaluable.

Notes

[1] In addition to these two cels from the “Vultures #81” batch, the Walt Disney Family Foundation, San Francisco preserves a third, very similar “large celluloid,” and a fourth, was sold by Heritage Auctions at its Animation Art Signature Auction #7295, Dallas, Texas, December 10, 2022, lot 17233.

[2] See, for instance, the Courvoisier cel set-up measuring 5.5 x 5 inches, sold at Heritage Auctions’ Animation Signature Auction 7193, New York, July 1-2, 2014, lot 94071.

References

Anon. n.d. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Vultures. https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/371922

Anon. 1939a. “Ferdinand the Bull advertisement.” The Kansas City Star. 27 March, 2.

Anon. 1939b. “Grim Disney.” Time. 6 February 1939, 42.

Anon. 1939c. “Snow White in a Museum.” New York Times. 25 January, 20.

Anon. 1939d. “Disney Joins the Masters in Metropolitan; Museum to Show ‘Snow White’ Watercolor.” New York Times 24 January, 17.

Anon. 1938. “The Magic of Walt Disney.” The Art Digest 12:13, 25.

Apgar, Garry. 2023. “Walt Disney and High Culture,” page proofs for a forthcoming issue of the Hyperion Alliance Annual (shared by author).

Apgar, Garry. 2015. Mickey Mouse: Emblem of the American Spirit. San Francisco: The Walt Disney Family Foundation Press.

Associated Press. 1939a. “Hail the New Master!” Poughkeepsie Eagle-News. 4 February, 6.

Associated Press. 1939b. “Metropolitan Museum to Hang Disney Painting.” Hartford Daily Courant. 30 January, 4.

Associated Press. 1939c. “Vultures Nose Out Walt Disney ‘Stars” for “Met’ Honors.” The (Glens Falls, New York) Post-Star, 30 January, 2.

Burchard, Wolf. 2021. Inspiring Walt Disney: The Animation of French Decorative Arts. New York, NY: The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Burroughs, Louise G. 1939. “Notes.” Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 34:2, February, 50.

Courvoisier, Guthrie. 1938a. “First National Showing and Sale of the Original Watercolors from

Walt Disney’s ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs.’” 29 August to 17 September. Courvoisier Galleries, 133 Geary Street, San Francisco [Exhibition Announcement]. Northern California Gallery Files, SFMOMA Library.

Courvoisier, Guthrie. 1938b. “‘Preferred’ Dealer Bulletin #1.” n.d., Washington, DC: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Doll & Richards gallery records, 1863-1978, bulk 1902-1969.

Courvoisier, Guthrie. 1939a. “‘Art History in the Making’ leaflet.” n.d. Washington, DC: Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Jay McEvoy papers, 1934-1995.

Courvoisier, Guthrie. 1939b. Letter to Edith Wakeman Hughes. 9 February. Archived document, State Historical Society of North Dakota, MSS 10114.

Hixon, Helen. 1939. Letter to Edith Wakeman Hughes. 17 October. Archived document, State Historical Society of North Dakota, MSS 10114.

Holian, Heather. 2023. “Always to the Highest Types of Individuals:” Edith Wakeman

Hughes, Disney Courvoisier Dealer to America’s Elite, 1939-42, to be presented at the Northeastern Popular Culture Society annual meeting, 14 October (virtual).

Holian, Heather. 2022. “Exhibiting Animation Art with an Agenda: Walt Disney Premiere Exhibitions of the ‘Golden Age.’” Presented at the Southeastern College Art Conference. Baltimore, MD. 28 October.

Hughes, Edith Wakeman. 1939a. Letter to Alex Tiers. 17 December. Archived document, State Historical Society of North Dakota, MSS 10114.

Hughes, Edith Wakeman. 1939b. Letter to Alex Tiers. 12 December. Archived document, State Historical Society of North Dakota, MSS 10114.

Johnson, Mindy. 2017. Ink & Paint: The Women of Walt Disney’s Animation, New York: Disney Editions.

Kaufman, J.B. 2012. The Fairest One of All: The Making of Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, San Francisco, CA: The Walt Disney Family Foundation Press.

Kent, H.W. 1938. “Gift Acknowledgement.” Disney, Walt, 1938-1939, 1946. Office of the Secretary Records. The Metropolitan Museum of Art Archives, New York.

Krause, Martin and Linda Witkowski. 1994. Walt Disney’s Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs: An Art in Its Making. New York: Hyperion.

Munsey, Charles. 1974. Disneyana: Walt Disney Collectibles. New York: Hawthorn Books, Inc.

Neuman, Robert. 1999. “‘Now Mickey Mouse Enters Art’s Temple’: Walt Disney at the Intersection of Art and Entertainment.” Visual Resources. 14:3, 249-61.

Nugent, Frank. 1939. “Disney Is Now Art—But He Wonders.” New York Times Magazine. 14:3, 4-5.

Watts, Steven. 1997. The Magic Kingdom: Walt Disney and the American Way of Life. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company.

Biography

Heather Holian is a Professor of Art History and Associate Director of the School of Art at the University of North Carolina in Greensboro, where she teaches classes on the art and artists of the Disney and Pixar Animation Studios. Heather is currently working on a book manuscript that investigates the history of early Disney art exhibitions (1932-66) and focuses on issues of American art and identity. Heather is also the Head of Mentoring & Membership at the Disney Culture & Society Research Network (DisNet).