Contagion Animation as Contagious Animation

There is no accounting for taste at the best of times, but this past month’s constant stream of dire global pandemic news and projections has wreaked havoc on streaming algorithms, as quarantined audiences scramble to keep themselves occupied with a wide variety of new content. While many have opted to dive headfirst into big cat-themed true crime, others are eschewing escapist entertainment in favor of a morbid fascination with newly relevant fictional contagion narratives.

Afraid of missing out on rehearsing our potential collective demise via pseudoscientific Hollywood fantasies, I took it upon myself to revisit animated contagion classics. There was, however, an unforeseen obstacle: I could not think of any. A social media query yielded only three features: Cowboy Bebop: The Movie (Shinichirō Watanabe, 2001), Seoul Station (Yeon Sang-ho, 2016), and Isle of Dogs (Wes Anderson, 2018). One of these is a prequel to the much better-known South Korean live-action zombie hit Train to Busan (Yeon Sang-ho, 2016). Another one is an extension of a beloved anime property. Finally, the true existential threat of Isle of Dogs lies not in its imaginary canine flu outbreak, but rather in the infectiousness of Anderson’s terminal twee.

This begs the question: are the boundaries of the cartoon somehow impervious to contagion? The short answer is no – as long as one is willing to push the genre boundaries and include edutainment, one can find many drawn examples of disease, from simplified child-friendly depictions of common health conditions, to more sophisticated, text-heavy frames that combine fictionalized representations of infectious agents with current medical information. The French children’s TV series Il était une fois... la vie (Albert Barillé, 1987), designed to introduce young viewers to the workings of the human body, features animated representations of viruses and bacteria. In a similar vein, David Production Inc.’s recent anime Cells at Work! (2018) centers on its anthropomorphic White Blood Cell protagonist’s bloody battles with various threats, including this Type B influenza virus (Fig. 1). Last but not least, fellow millennial scholars will likely remember the live-action/animation hybrid Osmosis Jones (Tom Sito & Piet Kroon, 2001), a school biology class staple whose cartoon sequences take place inside Bill Murray.

And yet, there has been no comparable surge in Osmosis Jones viewership numbers, and Cells at Work! remains a relatively niche choice even amongst anime fans. So where is the animated feature to rival Outbreak (Wolfgang Peterson, 2005)? I Am Legend (Francis Lawrence, 2007)? Contagion (Steven Soderbergh, 2011)? Why is there such a dearth of viral (with apologies, but no regrets) animated material to anxiety-stream during the end times?

The answer is hidden in multiplane sight. It’s not that contagion narratives are never animated. It’s that, in real life, they always are.

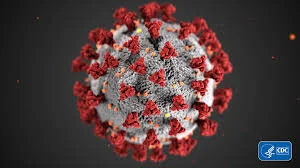

We have all been watching contagion animation every day – on the news, in various online publications, and on social media. From the earliest days of the epidemic, animated charts have traced the spread of the disease, their colorful bars racing towards an ever-grimmer tomorrow. 3D models of the virus (Fig. 2) have become instantly iconic, even cropping up in political collages. Some hospitals have released 3D imaging that visualizes the spread of the infection inside the human body to warn the general public of the dangers of covid-19. Experts have created animated gifs to illustrate the importance of social distancing. YouTube is already hosting a vast library of short explanatory cartoons meant to demystify the symptoms and effects of the disease. Every day, new sections of animated world maps become engulfed in unforgiving, inexorable red – a dark pandemic fantasy playing out in real time.

This extensive reliance on animation by news outlets and health organizations aiming to spread accurate, succinct information about covid-19 to the general public as quickly and efficiently as possible is neither surprising, nor unprecedented. The historical relationship between scientific visualization and cartoons has been well-documented (Gaycken 2014). Specifically, Gaycken highlights the educational impact of scientific animation which is “not representational in the sense of attempting to provide a fully mimetic experience, nor inventive in the tradition of animation’s tendency to create fantastic and metamorphic worlds,” but is instead designed to create “a selective reduction of visual information that leads to a clearer understanding of the phenomenon under investigation” (2014: 69). It is precisely animation’s capacity to convey (rather than simply report) objective knowledge through a visual language that can supersaturate fact without bleeding into fiction that is keeping it at the forefront of covid-19 coverage. While drawn representations of contagion could just as easily fuel fictional takes on the global pandemic (consider the terrifyingly prophetic 2012 simulation game Plague Inc.), animation is currently thriving within the realist mode of news cycles and public service announcements because this is the realm of social discourse where its particular epistemological powers are most relevant – and most needed.

As early as the 1920s, animation in America was already accepted as the ‘default medium for communicating information to the “average person” (Ostherr 2012: 126). A century later, animation remains an invaluable tool for conceptualizing an ongoing global crisis caused by an unseen threat and exacerbated by lack of reliable data and a general sense of confusion. In an environment saturated by mounting collective anxiety and uncertainty, turning to animation – a medium that gives shape to the invisible – is not simply convenient, but urgently necessary. There is a pressing need to visualize, plot, map out, and explain key aspects of our new normal in the most straightforward, easily communicable terms possible. After all, this is a disease whose containment and (hopefully) eventual eradication hinges largely on a coordinated group effort. Understanding how – and why – one must act on an individual level is half the battle.

Animating covid-19 coverage is not only a question of people’s safety, but also their emotional well-being. Cartoon imagery’s capacity to easily zero in on – and, crucially, emphasize – the essentials while trimming tangential or superfluous material becomes vital as the information overload of an oversaturated news cycle reaches critical levels. The sense of clarity afforded by animation is not, in this case, an aesthetic choice; it is a matter of public health, both physical and mental. When reality itself no longer feels real, photographic media simply cannot cut it.

Almost a decade ago, Suzanne Buchan noted that ‘animation is pervasive in contemporary moving culture’ (2013: 1). While this was certainly true then, it is especially salient in the current moment. We are living through a moment of relentless animation, perhaps even – dare I say it – contagious animation.

**Article published: April 17, 2020**

References

Buchan, Suzanne (ed.). 2013. Pervasive Animation. New York: Routledge.

Gaycken, Oliver. 2014. “’A Living, Developing Egg is Present Before You’: Animation, Scientific Visualizaiton, Modeling,” in Animating Film Theory, ed. Karen Beckman, 68-81. Durham: Duke University Press.

Ostherr, Kirsten. 2012. “Cinema as universal language of health education: translating science in Unhooking the Hookworm (1920).” In The Educated Eye: Visual Culture and Pedagogy in the Life Sciences, eds. Nancy Anderson and Michael R. Dietrich, 121-140. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press.

Biography

Mihaela Mihailova is a Postdoctoral Fellow at the University of Michigan Society of Fellows, with a joint appointment in the Department of Film, TV and Media. She has published in Feminist Media Studies, animation: an interdisciplinary journal, Studies in Russian and Soviet Cinema, and Kino Kultura. She has also contributed chapters to Animating Film Theory (with John MacKay), Animated Landscapes: History, Form, and Function, The Animation Studies Reader, and Drawn from Life: Issues and Themes in Animated Documentary Cinema. She is currently editing a collection of essays titled Coraline: A Closer Look at Studio LAIKA’s Stop-Motion Witchcraft for Bloomsbury Publishing.