Review: Venom (Ruben Fleischer, 2018)

When Sony announced that they were making a solo vehicle for Venom, one of Spider-Man’s most popular villains, independent of Spidey’s ongoing film series set in the Marvel Cinematic Universe, many fans were baffled. Not only is Venom an antagonist first and foremost, but more than any other villain his existence is predicated entirely on his relationship with Spider-Man. He is a dark inversion of Peter Parker, sharing his powers and his appearance, and his origin and motivation centre squarely around his hatred of the hero. And yet, while Venom (Ruben Fleischer, 2018) does manage to tell a surprisingly coherent version of its title-character’s origin without even a mention of Spidey, the excision of the anti-hero’s raison d’être does have a knock-on effect on the story’s themes. Specifically, it complicates the power-fantasy represented by Venom, an ordinary human whose strength and aggression is augmented by an alien parasite called a ‘symbiote’.

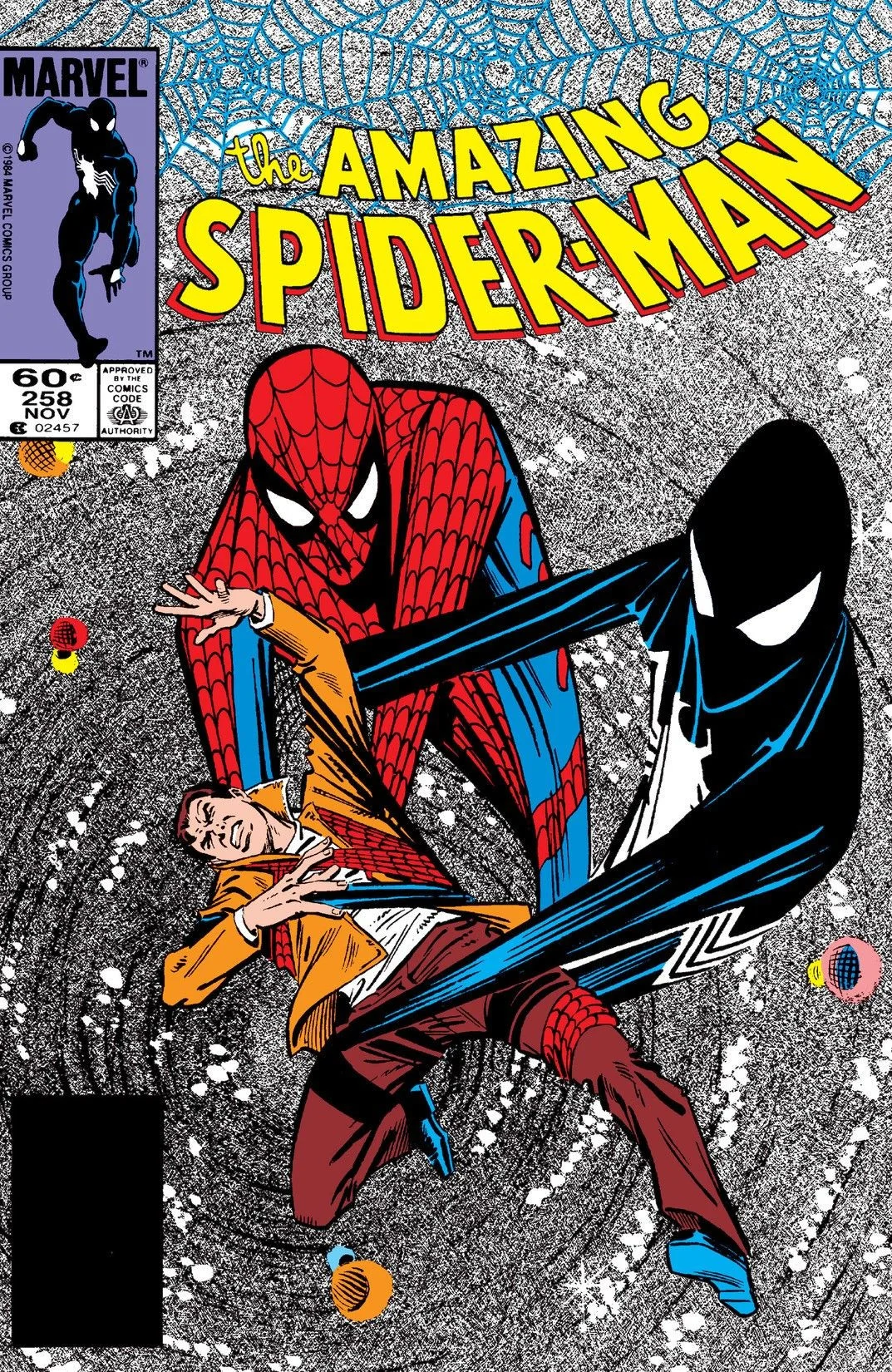

In the classic The Amazing Spider-Man comic-book saga (#252-263, 1984-85) (Fig. 1), later adapted into animation in Spider-Man: The Animated Series (1994-1998) and live-action in Sam Raimi’s Spider-Man 3 (2007), the symbiote is depicted as a primal creature, desirous of a strong host and exerting an aggressive influence, but largely beholden to the whims of its human ‘partner’. It initially bonds with Spider-Man, and allows him to fulfill his own fantasies, to a degree; its enhanced strength, unlimited supply of webbing and shapeshifting abilities make him a more efficient crime-fighter. Spider-Man 3 takes this a step further, as the suit also taps into Peter Parker’s fantasies, giving him the confidence to flirt outrageously with multiple women, demand more money for his photos from the Daily Bugle and, in one infamous sequence, hijack the piano for an elaborate dance number in a jazz club. In each of these versions of the tale, Peter eventually rejects the suit’s power and influence after realising its true nature, and the jilted symbiote attaches itself to Eddie Brock. Brock is a journalist, or sometimes a photographer, whose career is indirectly ruined by Spider-Man when he is revealed as a fraud. He harbours a deep hatred for, and jealousy of, the superhero, and finds a kindred spirit in the alien suit. The two merge to become the villain Venom, granting Eddie all of Peter’s powers and more, enabling him to enact his revenge fantasy while also satisfying his envy. Whether affixed to Peter or Eddie – or any of the various other hosts it bonds with in the comics – the Venom symbiote amplifies the characteristics of its partner, bringing their negative emotions and darker desires to the forefront and allowing this to inform the actions of their aggregate body (Fig. 2). In this way, the suit is a straightforward parable warning against male power fantasies and, in particular, unchecked aggression as a means to an end. Peter rejects the symbiote because it drives him to use more violent crime-fighting techniques, and in Spider-Man 3 his womanising and violent outbursts also alienate his love-interest, Mary Jane. Eddie, meanwhile, believing himself to be a better hero than Spider-Man, styles himself as a ‘lethal protector’, killing, maiming, and often cannibalising criminals to satisfy his sense of self-worth. In doing so, however, he sacrifices his sense of self. In giving himself over to the symbiote’s power he comprehensively merges with it in a way Peter never did, made clear by his use of the pronoun ‘we’. Eddie loses his identity as an individual in the process of indulging his power fantasies, and displays symptoms of addiction and withdrawal whenever he loses the suit. A hulking bodybuilder even before he became Venom, once stripped of the symbiote Brock is emaciated and weak.

All this is to say that, in removing the Spider-Man character from the symbiote’s story, the film version of Venom flattens and reverses the dynamics of its protagonist’s relationship with the alien suit. In the film’s version of events, instead of Spider-Man, Eddie (Tom Hardy)’s career is ruined by Carlton Drake (Riz Ahmed), an evil tech CEO who is harvesting symbiotes and testing them on homeless people. Eddie confronts him on this in a live interview and is shut down, leading to him losing both his job and his fiancée, Anne (Michelle Williams). His life in shambles, Eddie is initially motivated by fantasies of revenge against Drake, but this goes out of the window when he breaks into his lab and accidentally merges with the symbiote. Without their shared hatred of Spider-Man, Eddie and the suit have no common goal to unite them and provide them with a motivation. Instead, the film becomes the story of Eddie – here portrayed as a pathetic, shifty loser as opposed to the strong-willed bruiser of the comics – struggle to cope with the parasite living inside him. To compensate for this lack of shared motivation, and to explain much of the character’s actions and unusual, aggressive behaviour, the symbiote is given much more agency than in most earlier iterations (Fig. 3). It speaks directly to Eddie, more often than not arguing with him, either as a voice in his head or as a face protruding snake-like from his torso. It has its own backstory – apparently, on its home planet it was a ‘loser’ like Eddie – and its own personality. Notably, this personality is essentially that of the aggregate ‘Venom’ persona from the comic books, displaying the aggression, naivety, crude humour and warped sense of justice associated with the character. While the comic Venom is very much a product of symbiosis, with the suit augmenting qualities already present on some level in Brock himself, in the film this persona is simply assigned to the alien, who in turn uses Eddie’s body to enact it. While he still speaks the character’s catchphrase ‘We are Venom’, the ‘we’ here is entirely superficial, as never do the two characters truly speak or act as one.

Instead of a symbiotic entity which enables a human protagonist to enact their darkest fantasies, if anything Venom is manipulating Eddie, both mentally and physically, to enact its fantasies. In the run-up to Venom’s release, much was made in of an interview in which Hardy claimed his favourite moments were cut from the film, among which were apparently ‘mad puppeteering scenes’. Who can really say what was meant by this (though it certainly conjures a vivid image of Venom re-enacting his favourite scenes from Thunderbirds), but it could well be that Hardy was referring to the manner in which the symbiote uses Brock’s body as a puppet. Even before it manifests itself as Venom, covering its host completely, the alien lives inside of him and periodically seizes control, throwing him into a lobster tank looking for food, or propelling him through a high-speed motorbike chase. While obviously an animated creation itself, the symbiote is also the animator here, as Hardy gamely conveys his character’s lack of agency through a series of pratfalls and bemused, increasingly resigned, expressions.

Neither the relationship between Brock and the suit, nor their individual motivations and desires, are given much room to develop in a film which appears to have left much of its second act on the cutting room floor, but we are given enough information to see that Venom’s goals supersede Eddie’s by the narrative’s conclusion. Brock does not reconcile with his fiancée, save for a brief, disturbing kiss instigated by the symbiote possessing, and hyper-sexualising, Anne’s body. He doesn’t even, really, get his revenge on Drake, as his plan to go public with photographic evidence of the CEO’s crimes is abandoned with little fanfare halfway through the film. Drake only becomes a priority for Venom once he merges with Riot, a bigger, badder symbiote who was his ‘team leader’ on their home planet and towards whom he seems to bear an ill-defined grudge. Only then does the suit use Eddie’s body to dispose of both of their enemies. As the film ends, with Venom devouring a gangster who had troubled Eddie’s friendly neighbourhood shopkeeper earlier in the film, we see that Brock and the symbiote have developed a clear working relationship (Fig. 4). Eddie will allow the symbiote to enact its violent fantasies – which it described in grizzly detail before eating the man – but only upon criminals who deserve it. Like in the comics, Venom has become a ‘lethal protector’, but not as a manifestation of the vigilante power-fantasies of its host. Any flaws or dark desires that Eddie may have had as a character go unaddressed; he is simply a reluctant vessel for a wanton alien entity that he cannot really control, only bargain with. Unlike his comic counterpart, he bears little responsibility for Venom’s actions, and as such the audience is never asked to confront the desires that might drive a man like Eddie to willingly cede his body to this creature.

Biography

Sam Summers is Associate Lecturer in Film at Liverpool Hope University. His research focuses on the use of intertextual references in contemporary animation in general and DreamWorks’ animation in particular, with a view to contextualizing and historicizing the studio’s role in the development of the medium. He is the co-editor (with Noel Brown and Susan Smith) of Toy Story:How Pixar Reinvented the Animated Feature (London: Bloomsbury Academic,2018), and has a forthcoming monograph on the DreamWorks Animation studio.